Seabird Counting

Seabird CountingAuthor: Roy Gosney, GuideDate: August 2024Photo credit: Oscar Thomas There is no doubting the success of Tiritiri Matangi in preserving bird species that have principally succumbed to human devastation. This achievement however provides no indication of how more successful species are faring. Enter the ubiquitous seabirds whose status is a good indicator of overall ecological health, given their existence on the margins of land and sea. A little-known project on Tiritiri Matangi has been Seabird Counting, the aim of which is to help fill this gap in our knowledge. Seabird counting has been an annual event taking place between September and January and is in its 12th year. Mike Dye did this for the first 10 years ably describing his experience in a 17th May issue of Guidelines. I assisted Mike over the last 5 years until we were joined by Rachel Taylor. Rachel and Mike, now no longer in Auckland, left a vacuum that I, in a mad moment, agreed to fill. Consequently, I started the 23-24 season on my own, but thanks mainly to Mike’s article, a number of people have come forward and we’ve built a good team comprising: Scott Camlin, Bethny Uptegrove, Sue Beaumont Orr, Yvonne Vaneveld and Julie Benjamin. The target species are primarily Red-billed Gulls (RBGs), Black-backed Gulls (BBGs), White-fronted Terns (WFTs) and Pied Shags (PS) because…

Birds—The Formula 1s of the Animal World

Birds—The Formula 1s of the Animal WorldAuthor: Malcolm Pullan, GuideDate: July 2024Photo and video credit: Neil DaviesHave you ever marveled at the extraordinary journeys that some birds go on when they’re feeding or migrating? Have you ever wondered how birds are able to fly through the forest so quickly, yet not crash into things? Have you ever wondered how it is that many birds can remain on the ground as a car is approaching and then quickly escape at the very last second? You haven’t? Oh well, neither had I until a few years ago. Now, though, I think about it almost every time I see a bird. For I now know that underpinning these observations is something quite special about birds that explains so much about why birds are the way they are. Birds are hot(1). In fact, they’re the hottest vertebrates (2) around. You and I maintain a more or less constant body temperature of around 37°C. That’s fairly typical for a mammal. Birds also maintain a relatively constant internal body temperature—except theirs is likely to be in the range of 39– 43°C, i.e. quite a bit higher than your average mammal. Now you don’t need to know much chemistry—or baking for that matter—to know that when you heat things up, chemical processes speed up. This is what happens in birds. Stuff happens more quickly. For instance, reaction times are faster and muscles can work harder.…

Highway robbery

Highway robberyAuthor: Jonathan Mower, GuideDate: July 2024Photo and video credit: Jonathan Mower This short video clip captures a moment of interspecies interaction when a toutouwai/ North Island robin came across a tīeke/ North Island saddleback that had captured and killed a wētā. The toutouwai was a much more dominant bird and harassed the more timid tīeke, eventually causing the tīeke to abandon its prey to the toutouwai which snatched it and flew away. The small wattles and timid nature may mean the tīeke was a young and inexperienced hunter because I have previously seen tīeke aggressively dispatch large prey including hura/giant centipedes and wētā. By nature, the toutouwai are often bold and aggressively territorial toward others of their own kind but here we see them interacting and showing dominance over a very different species.

With Matariki approaching, it is an opportunity to look back and look forward

With Matariki approaching, it is an opportunity to look back and look forwardAuthor: Ian Alexander, Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Island ChairDate: June 2024Photo header credit: Geoff BealsWith Matariki approaching, it is an opportunity to look back and look forward, celebrating the past year and thinking of what can be achieved over the next year. It has been a year of change for volunteers and staff on and off the Island. Having farewelled two of our beloved members late last year, we remember them – Ray Walter and Mel Galbraith, two men who contributed a life of service in many different ways to the development of our island conservation project. And there are others who have passed away during the year who in their own way have also contributed to the work of the Island. Guiding both public and schools has continued to be a major part of the operations of Tiritiri Matangi as have efforts made by all our sub-committees and task groups across biodiversity, infrastructure, advocacy, education, fundraising, membership, retail and IT. Climate has and will continue to dominate the Island ngahere and tracks requiring constant attention by our regular working parties and individuals. Looking forward there remains much to do to ensure the proper care and attention to the Island’s flora and fauna and to continue to provide opportunities to everyday…

Meet the volunteers: Keeping it in the family – Davina, Diane and Bob

Meet the volunteers: Keeping it in the family – Davina, Diane and BobAuthor: Davina BennettoDate: June 2024My time on Tiritiri Matangi started during the pandemic when my job in the travel industry quickly went from ‘very busy’ to ‘dead quiet’. With my wonderful parents Bob and Diane already volunteering on the island, it was something I too was interested in but never had the time – oh how quickly things can change! I registered interest and soon found myself working in the shop, caught up in the magic that is our little slice of paradise, realising just how therapeutic Tiritiri Matangi was. From witnessing takahē walk into the shop to seeing a pīwakawaka flying in only to sit on a coaster with a pīwakawaka on it, things you wouldn’t experience every day, I always left the island feeling a million times better.

Tuatara—Ancient Escape Artist

Tuatara - Ancient Escape ArtistAuthor and photo credit: Jonathan MowerDate: June 2024Tuatara are the sole surviving member of an entire order of animals, the Rhynchocephalia, whose ancestors separated from those of the Squamata (lizards and snakes) in the late Triassic period, so about 240 – 250 m years ago. Reaching total lengths of over 600mm, they are the largest of New Zealand’s endemic, terrestrial reptiles (some males recorded at a hefty 1.1kg), with their ridged tails accounting for slightly more than half of that total body length. Muscular and powerful, the tuatara’s tail plays a significant role in balancing locomotion, storage of body fat, and displays of dominance or physical defence. To a superficial observer, the tuatara might be described as resembling a lizard, but in reality, there are significant differences between tuataras and other reptiles. One similarity, however, is the ability to sever deliberately and then regrow part of their tail. The practice is known as caudal autotomy and is a defensive mechanism that allows them to escape harm or predation. Why would you intentionally drop off part of your body? On their island sanctuaries, kahu/harriers are significant predators of tuatara. They are also predated by other birds including karearea/falcons, kōtare/kingfishers, and possibly, ruru/ morepork and karoro/black backed…

Tuatara—a three-eyed monster?

Tuatara - a three-eyed monster?Author: Malcolm PullanDate: May 2024Header image: Jonathan MowerWhen I was a child, I remember my dad telling me that tuatara had three eyes, with the third one on top of its forehead. I can still see the way my dad pointed to his forehead when he said that. I didn’t know what to make of it then: My dad often told outlandish stories. Was this one really true? Over the years when I saw tuatara at zoos, I would look at the top of their foreheads searching for that third eye. I couldn’t see it, and so I became a skeptic. When I became a guide on Tiritiri Matangi a few years ago I remember some other guides mentioning the third eye of tuatara. They said it in a way that made it seem like it was a unique oddity of a unique living fossil as if it were something only tuatara had. It all seemed fanciful so I set about finding out for myself and what I discovered is that the truth is even stranger than the hype. First, then, some basic facts. Tuatara do indeed have a third eye—complete with a lens and retina (i.e. with cells that detect light). This eye is positioned in the middle of the forehead, behind a small hole in the skull. My dad was right after all! Tuatara really do have a third eye in the middle of the forehead. It’s called the parietal eye (pronounced pa-rye-e-tal) (1). So why can’t we see this eye? It…

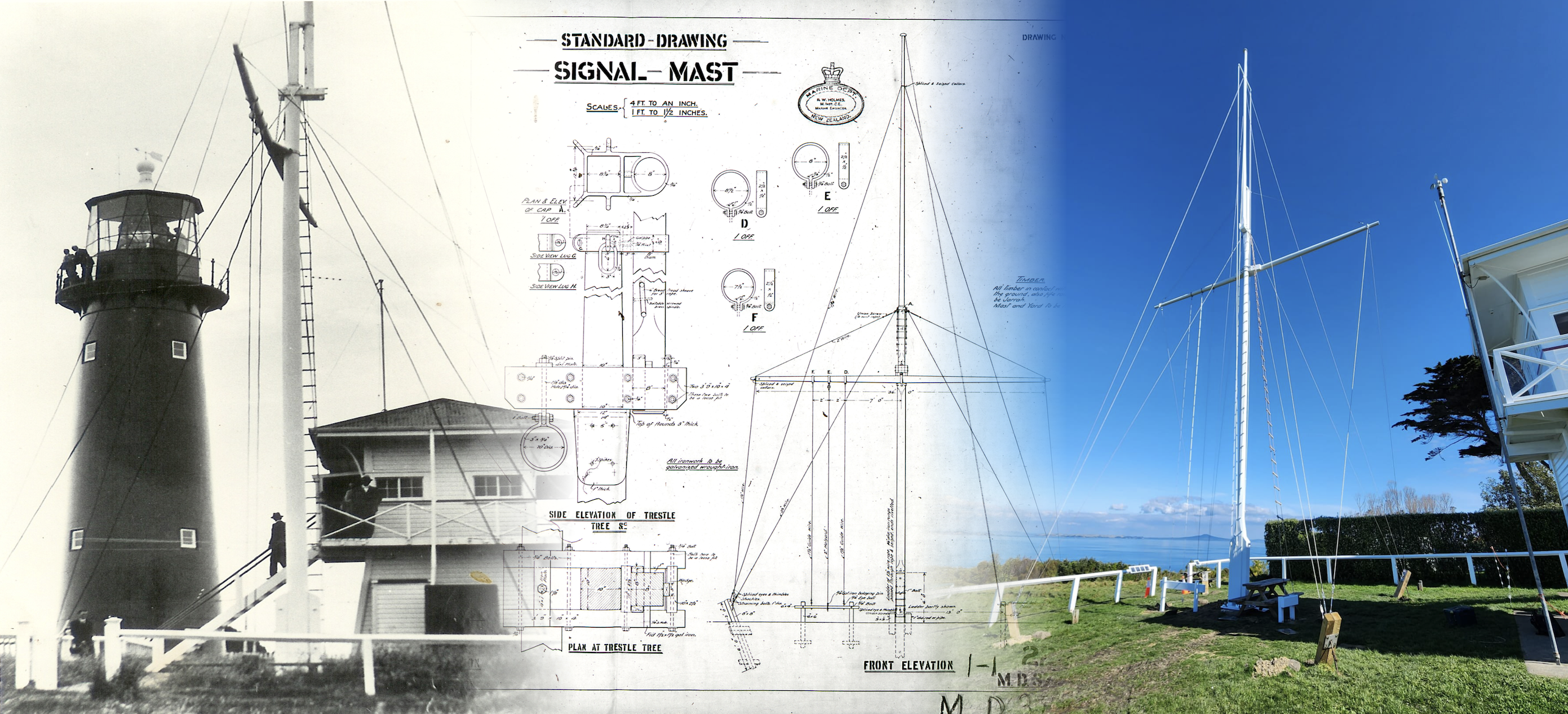

Tiritiri Matangi Island Signal Mast Reconstruction

Tiritiri Matangi Island Signal Mast ReconstructionAuthor: Carl HaysonDate: Taken from the Dawn Chorus, 135 November 2023Header photo: Geoff BealsThe replica mast has been rebuilt to the exact specifications of the original structure which was erected in the late 19th century. It last existed in the 1940s but, along with all the other signal masts on lighthouse stations around the country, was taken down when manual signalling was no longer required. In the early 2000s, SoTM restored the 1908 watchtower which had fallen into disrepair, and this is now a popular attraction for visitors. The mast was an integral part of the original signal station, and when Ray Walter and Carl Hayson discovered a small section of the old mast in 2003, a plan was conceived to rebuild it.

Its original function was to provide shipping information to the Ports of Auckland in the days before wireless transmitters were available. Signalling was conducted with a combination of flags and woven baskets which were seen by a station on Mt Victoria in Auckland. At 25m tall, the mast is slightly higher than the lighthouse and can easily be seen from the sea.

The kiwis are here

The kiwis are hereFrom the Tiritiri Matangi ArchivesEditor: Zane BurdettBulletin No.14Date: August 1993In fact, since the five pairs of little spotted kiwi arrived, they’ve been here, there and everywhere on Tiritiri – exploring what is now their new home. They arrive on the 4th of July – ‘Kiwi Independence Day’. That day, over 500 people; babies, children, teenagers, adults, young and old, officials, sponsors, scientists, reporters and Yamagata whenua – had waited. They had waited together on a ridge under a great cloudy sky with a cool wind blowing – but the wait was worth it! The was the first public release of the little spotted kiwi. Maybe on this day the number of people in recent history to have seen a living little spotted kiwi in the feather had probably doubled! The kiwis arrive by helicopter at about 3pm accompanied by representatives of Ngtai To a and Te Ottawa, tangata whenua of Kapiti Island, the Minister of Conservation Mr Denis Marshall and DoC staff. They were greeted by representatives of Te Kawerau a Maki, tangata whenua of Tiritiri Matangi. Following speeches by officials and Dell Hood and Mel Galbraith – 4 birds were taken by DoC staff and shown to the gathering. All the birds were taken to their released sites and placed into prepared burrows. The arrival of the little spotted kiwi on Tiritiri was made…

Pukupuku/little spotted kiwi

Pukupuku/little spotted kiwiAuthor: Jonathan MowerDate: May 2024Header image: John Sibley Island visitor Darren Markin recently captured this footage of a foraging kiwi pukupuku/ little spotted kiwi, while walking one night along Tiritiri Matangi’s Ridge Road. Being nocturnal by nature, footage of active kiwi is relatively uncommon, so his footage is a rare record of kiwi’s feeding behaviour. Kiwi pukupuku/little spotted kiwi are the smallest of the 5 surviving kiwi species, with the larger females averaging 1350g/30cm. Once widespread in both the North and South Islands, human arrival in New Zealand saw them disappear from both islands and the species diminished to only a small population on Kapiti Island, the descendants of a small number translocated there in 1912. Descendents of these survivors were first translocated to Tiritiri Matangi in 1993 when five pairs were transferred from the Okupe Valley, Kapiti Island to Tiritiri Matangi Island on 4 July 1993. Subsequent translocations have boosted their numbers on the island to the point that their calls are regularly heard and, as Darren’s video attests, seen by visitors walking at night. This video is particularly useful in showing how kiwi forage for food. Kiwi use their bill to detect their prey (mostly small invertebrates such as earthworms and insect larvae) and are often observed moving through…