Fifty years since the translocation of kākāriki/ red-crowned parakeet

Fifty years since the translocation of kākāriki/ red-crowned parakeet

Fifty years since the translocation of kākāriki/ red-crowned parakeet

Author: Dick Veitch New Zealand ecologist and ornithologist

From the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Archives: Dawn Chorus, 138, August 2024

Header photo credit: Geoff Beals

To celebrate this milestone, we asked Dick Veitch, who was involved in the translocation, to share his memories of that time.

Visitors to this island haven have now seen kākāriki as they surely were over mainland New Zealand before the arrival of humans and their accompanying pests.

On Te Hauturu-o-Toi / Little Barrier Island, kākāriki survived with cats and kiore as predators. On the Hen and Chicken Islands, they survived with only kiore as a predator. On Macauley Island, they survived with goats and kiore and no trees, but on nearby forested Raoul Island, they were eradicated by a combination of goats, cats, and two rat species. When the goats were eradicated, kākāriki were again present in the forest, but we doubt that they were breeding. When the cats and rats were also removed, kākāriki were again abundant birds in the forest.

Like so many of our birds, kākāriki have two basic needs to overcome when faced with predation and competition: food and nesting. One of their preferred feeding habits is to scavenge for fallen seeds among the leaf litter. In this, they compete with kiore, who also scavenge for seeds. Ground- feeding also makes them susceptible to predation by cats.

It seems they can survive both of these threats if there are no goats present to remove the forest understory and most of the leaf litter, thus making it easy for cats to hunt. It also seems that kākāriki can defend their nests against kiore, but not against larger rats.

That readily explains the absence of kākāriki from many islands, but not Tiritiri Matangi, which had only kiore and always had some forest. We presume kākāriki were present but have no proof of this as Tiritiri Matangi, like Cuvier and a few other islands, was not often visited by ornithologists.

By the late 1960s, staff in the Wildlife Service, later to become part of the Department of Conservation, were attempting to actively improve our offshore islands by removing goats, sheep and cats and returning missing bird species. Kākāriki were proposed for re-introduction to Tiritiri Matangi and Cuvier, but there was controversy over the source of birds to release. Some aviculturists, who had stocks of captive kākāriki, wanted their birds to be used. Others in the decision chain stalled, on the grounds that such aviary-bred birds were cross-breeding between red and yellow-crowned species. It was then determined that the kākāriki taken from Hen Island to Mount Bruce Native Bird Reserve was a pure strain and thus suitable for the purpose. In January 1974, a consignment of approximately 30 kākāriki was sent from Mt. Bruce to Auckland, for liberation on Cuvier Island. Chris Smuts-Kennedy, Wildlife Service, duly took them off by road to Whitianga but, when he got there, the boat was not in the harbour and the sea was too rough for others to venture out. The birds were taken to an aviary in Auckland for a few days of rest before being taken by Wally Sander, Chief Ranger, Hauraki Gulf Maritime Park, and Chris to Tiritiri Matangi and released.

As we had hoped, they established themselves on the Island. There was just one problem. A member of the public made an accusation, to the Wildlife Service at least, that the lighthouse keeper on Tiritiri Matangi was catching kākāriki and selling them. We could not establish any truth in this accusation and concluded it may have come from a miffed aviculturist.

Tree planting began on Tiritiri Matangi in 1984, and Mike Graham, with members of the Ornithological Society, started bird counts in 1987. By that time, the kākāriki population was well established and probably growing, as the island environment changed with time and the planting programme.

From 1990 to 1992, kākāriki comprised 4.9% of the birds counted on the ‘forest transects’. Kiore were removed from the Island in 1993. From 1996 to 1998, kākāriki comprised 7.3% of the birds counted on the same transects. This was a 177% increase in the number of kākāriki counted, but it appeared to be less of an increase than the general bird population on the Island. There was a noticeable abundance of korimako/bellbirds and tīeke/saddlebacks at the same time. For all these species, the big benefit was the removal of a food competitor.

I hope that kākāriki and all other birdlife on Tiritiri Matangi continue to be a joy for all to behold for a very long time to come.

Left image: credit Hilda Mikaelsson

Right image: Jonathan Mower

Mammals (Part 3): Mammals in Pre-Human New Zealand

Mammals (Part 3): Mammals in Pre-Human New Zealand

Mammals (Part 3): Mammals in Pre-Human New Zealand

Author: Malcolm Pullan, Volunteer Guide

If you’re a New Zealander you will “know” that prior to the arrival of humans there were no mammals in New Zealand apart from bats. “Knowing” this is part of the DNA of being a New Zealander, like knowing that kiwi don’t fly and the All Blacks play rugby. However, if you had no connection with New Zealand whatsoever, and just so happened to have read Parts 1 and 2 of this series of articles on mammals, you wouldn’t be expecting that answer at all. You would be expecting me to say there are, or at least, were mammals in New Zealand (apart from bats) prior to the arrival of humans. And you would be perfectly right—and most New Zealanders perfectly wrong. New Zealand did indeed have mammals (other than bats) prior to the arrival of humans.

You don’t believe me? Not even if I say it with a smile? Let me try and convince you in other ways then…

Let’s summarise where we got to in the previous articles. Once upon a time New Zealand was joined to Australia and Antarctica. New Zealand began to separate from Australia/Antarctica about 105 MYA (million years ago) and continued to do so until sea completely separated them about 80 MYA, with the gap increasing substantially over the next 20+ million years. Globally, mammals evolved about 205 to 210 MYA. Mammals have been in Australia right from beginning of mammal-dom (1), starting with monotremes (i.e. mammals like the platypus and echidna), followed by some long since extinct lineages that I’ve informally called Allotheria (and whānau). Marsupials and placentals (the predominant mammalian lineages today, especially the latter) didn’t arrive in Australia until much later, almost certainly well after New Zealand separated from Australia. Monotremes and Allotheria (and whānau), on the other hand, were definitely in Australia when New Zealand and Australia were still joined. There is every reason to believe that New Zealand took some of these sorts of mammals with it when it broke away. Indeed, it would be very odd if it didn’t.

This is precisely why I have written parts 1 and 2 of this series. I could have easily written this present article without the others (now he tells me!). But if what’s being said here is going to bust a myth, then I’ve got some explaining to do about why busting the myth makes sense. I need to explain why it shouldn’t be a surprise that the myth is indeed a myth, i.e. it isn’t true.

I repeat. New Zealand did indeed have mammals (other than bats) prior to the arrival of humans. The evidence for this is actually quite simple and concrete (rock, to be precise). It is some mammalian fossil bones from about 16 to 19 MYA that were reported in a scientific paper in 2006 (2) This isn’t some obscure paper by some second-rate amateurs, but a mainstream article by Trevor Worthy (and team), one of the most respected professional palaeontologists working in the New Zealand field today. It is a bonafide and convincing result. Mammalian fossils dating from about 16 to 19 MYA have been found in New Zealand.

So what was this mammal like? For a start, it was very small. It was only about mouse-size. However that’s where the comparison with mice ends. Mice are placentals. This “not-a-mouse” (3) probably belonged somewhere in the now extinct group of lineages I have called Allotheria (and whānau) (4). Where in that group, though, is anybody’s guess. “Not-a-mouse” appears to be from a unique mammalian lineage that nobody knew about before. Not only that, as far as is currently known, all Allotheria (and whānau) lineages elsewhere in the world died out millions of years before “not-a-mouse” was alive. In other words, this New Zealand mammal was probably an ancient relict—a mammal of a type that had long since become extinct elsewhere. That New Zealand had such an ancient relict shouldn’t be a surprise. After all, this is precisely what the tuatara is in the reptile world.

It should also not be a surprise that “not-a-mouse” was a member of Allotheria (and whānau), rather than a marsupial or placental. According to Trevor Worthy and team, the most likely explanation for the existence of “not-a-mouse” is that it belonged to a population of mammals that had been in New Zealand continuously since it separated from Australia. Marsupials and placentals wouldn’t have been in this population because they weren’t in Australia at the time of separation.

So what happened to the mammals that were in New Zealand after it separated from Australia up until the time of “not-a-mouse”? Well, clearly they became extinct. (5) The next question is why? Why did they become extinct? One common explanation for pre-human extinctions in New Zealand is loss of habitat. New Zealand sank after it broke away from Australia and a lot of land disappeared into the sea. However the low point of this sinking was about 22 to 25 MYA. (6) “Not-a-mouse” comes from 16 to 19 MYA, so mammals clearly survived past this low point. Instead, the extinction of mammals in New Zealand was probably caused by global climate change. This isn’t the recent extremely rapid human-made global climate change, but a very much slower and more extensive change that occurred after 16 MYA (cooling in this case). (7)

Next question. Why has it taken so long for (non-bat) mammal fossils to appear in New Zealand? There is a fairly simple answer for this. New Zealand is very frustrating when it comes to fossils. While there are tons of very recent fossils (or pre-fossilised remains because they’re so recent) and tons of fossils of sea creatures, there are almost no older fossils of land animals at all. It is only relatively recently that a small patch with a decent selection of such fossils has been found, and then even more recently excavated and studied (with work still very much in progress—watch this space!). This patch is near St Bathans in Otago. “Not-a-mouse” was found here.

In summary then, New Zealand almost certainly had mammals when it broke away from Australia. In fact New Zealand has almost certainly had non-bat mammals for most of the time since then. The sole non-bat mammal that has been discovered so far was small and probably belonged to a lineage totally distinct from the modern successful mammalian lineages that rule the world today. Not only that, it survived in New Zealand long after any remotely similar mammals remained elsewhere in the world (like the tuatara in the reptile world). It became extinct sometime after about 16 MYA, probably because of global cooling. Mammalian fossils have only just been found because New Zealand has an extremely poor fossil record of land animals, apart from the very recent past. While these conclusions may well bust a New Zealand myth, there is nothing unexpected about the results from a rational point of view. They are completely in keeping with, and to be expected from wider global stories of geology and evolution.

Figure 1: Palaeontologists excavating in the region where the mammal fossil was found (near St Bathans in Otago)

One final musing before I let you go. If, as seems likely, “not-a-mouse” was descended from mammals that were in New Zealand when it broke away from Australia, then many of our New Zealand birds will have evolved in the presence of mammals e.g. moa, kiwi, New Zealand wrens (e.g. rifleman) and the New Zealand wattle birds (e.g. kōkako). (8) How does this fit into the argument—and indeed much practical observation—that New Zealand birds don’t cope well with mammals? In the first place, the ancient New Zealand birds would have initially evolved alongside the New Zealand mammals. They had plenty of time to get used to each other, unlike contemporary New Zealand birds and recent placental arrivals. In the second place, if global cooling is the culprit in causing the extinction of New Zealand’s non-bat mammals, then it’s most likely they became extinct several million years ago, rather than comparatively recently. This will have given New Zealand birds plenty of time to forget about mammals altogether. Thirdly, the sort of mammals that New Zealand birds don’t cope at all well with are killing machines like rats, stoats and cats, and to a lesser extent mammals like deer, possums and rabbits. These are all placentals. “Not-a-mouse” was totally different. It was survivor from the days when mammals were small and largely kept in check by pesky dinosaurs. Perhaps, like the tuatara, New Zealand mammals retained their ancient features and were never much of a threat to birds in the first place?

I started this series of articles on mammals with a statement that many of us guides say to our visitors when they arrive on Tiritiri Matangi in order to explain the unique flora and fauna they’re about to see: “New Zealand broke away from the rest of the world about 60 MYA before mammals evolved.” Having completely demolished that statement on three accounts, what should we say instead? How about, “New Zealand broke away from the rest of the world about 80 MYA before modern mammals like rats and stoats evolved with their ruthless efficiency at killing”? What do you think we should say? Suggestions on the back of a postcard please!

P.S. A video

If you want to see the fossils of “not-a-mouse”, the paper by Trevor Worthy and team has photos (which can’t be reproduced here for copyright reasons). Alternatively, check out this video from Te Papa (Museum of New Zealand): https://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/topic/2918. (Caution: you may be disappointed when you see the fossils—you have been warned!)

P.P.S. A word on bats

Bats, like birds, have wings, and so a watery ditch isn’t going to be as big an obstacle to cross as it is for other land mammals. So it’s not surprising New Zealand had bats prior to human arrival when it didn’t have any other placentals. New Zealand has two types of bats, long-tailed and short-tailed, represented by just two living species today. (9) The long-tailed bat is nothing special from an evolutionary point of view. It arrived in New Zealand about 2 MYA and has close relatives in Australia and surrounding islands (e.g. New Guinea and New Caledonia). The short-tailed bats are much more unique. In Part 2 of this series on mammals I mentioned an Australian bat fossil from about 26 MYA. Lo and behold this bat was a relative of New Zealand’s short-tailed bats, so it seems likely that the New Zealand short-tailed bats came from Australia at some point. Any Australian relatives, though, are long since extinct. The closest living relative of New Zealand’s short-tailed bats today are in South America, but it’s a very distant connection indeed. This would make sense, given that the Australian bats are thought to have originated in South America.

Figure 2: New Zealand short-tailed bat

Referencing:

1 My made-up word for the day. Will it go viral and make it into the Oxford Dictionary, I wonder?

2 Worthy, T.H., Tennyson, A.J.D. et al. (see references for more details).

3 There is still no formal name for this animal. Informal names in use include “St Bathans mammal” (after where it was found—see text) and “waddling mouse” (after the fact that its legs were probably somewhat out to the side like a crocodile’s rather than directly underneath like a real mouse).

4 I say “probably” because it can’t be completely ruled out that it isn’t a monotreme or therian (the lineage including marsupials and placentals). It just isn’t statistically very likely (which is as good as it often gets really when working out where different animals sit on the evolutionary tree of life).

5 Or did they? Ever since the days of Captain Cook there have been reports of a “New Zealand otter”, with the last claimed sighting being in 1973. However “no positive evidence exists, only fleeting glimpses, usually from trout fishers or duck shooters” (Gibbs, Ghosts of Gondwana, p. 27). Also, if it really did exist, “it is much more likely to have been an aquatic monotreme than an otter” (Gibbs, p. 27).

6 This is known as the Oligocene drowning. A few years ago there was intense debate about whether New Zealand disappeared completely under the sea at the low point, but it is now more or less certain that at least some land remained, albeit not very much.

7 This massive global cooling was largely caused by the separation of Antarctica from Australia and South America. This separation created the ocean current known as the Antarctic Circumpolar Current circulating the globe unobstructed in the southern polar region. When this current formed it put a stop to the mixing of the southern polar seas with warmer tropical ones that had been operating for millions of years. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current created the cold Antarctic that we know today.

8 But probably not more recent arrivals, e.g. takahē and tūī.

9 The long-tailed bat and the lesser short-tailed bat. There is possibly another short-tailed bat alive, the greater short-tailed bat, although the chances of it still being around are slim. It hasn’t been seen since 1967. See https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/native-animals/bats-pekapeka/short-tailed-bat/.

References:

Gibbs, G. 2016. Ghost of Gondwana: The History of Life in New Zealand (revised edition). Potter &

Burton, Nelson. (pp. 27–28, 38–40, 83–86, 121–122, Chapter 10)

Lomolino, M.V., Riddle, B.R. & Whittaker, R.J. 2018. Biogeography: Biological Diversity across

Space and Time (5th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA. (pp. 261–262)

Pough, F.H, Bemis, W.E, McGuire, B. & Janis, C.M. 2023. Vertebrate Life (11th ed.). Sinauer

Associates, New York. (p. 445)

Thomsen, T. 2021. The Lonely Islands: The evolutionary phenomenon that is New Zealand. Reed

New Holland Publishers. (pp. 94–96, 194–196, Chapter 8)

Worthy, T.H., Tennyson, A.J.D. et al. 2006. “Miocene mammal reveals a Mesozoic ghost lineage on

insular New Zealand, southwest Pacific”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the

United States of America 103(51), pp. 19419–23. (This article can be downloaded here:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1697831/pdf/zpq19419.pdf)

Picture credits:

• Figure 1: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saint_Bathans_Miocene_Fossil_Site_NJR.jpg

(Wikipedia, shared through Creative Commons licensing).

• Figure 2: https://www.doc.govt.nz/nature/native-animals/bats-pekapeka/short-tailed-bat/

(Department of Conservation, shared through Creative Commons licensing).

Mammals (Part 2): Evolution of Mammals

Mammals (Part 2): Evolution of Mammals

Mammals (Part 2): Evolution of Mammals

Author: Malcolm Pullan, volunteer guide

Date: October 2024

According to a very unscientific survey carried out by examining my gut feeling, many people can answer the question, “When did mammals first appear?” Further similar unscientific analysis reveals that most of these answers will be something like, “About 60 MYA (million years ago), when dinosaurs became extinct”. Unfortunately, this common answer is incorrect (in fact, it’s not even true either…).

The purpose of this article is to put the record straight—and to give a little evolutionary history of mammals as whole, concluding with a little look at the evolutionary history of Australian mammals. The story of New Zealand mammals will follow on from this in final part of this series of articles.

Before beginning the discussion, I should warn you that the evolutionary history of mammals is an ever-changing minefield. There are controversies over dating and controversies of definitions and names of different groups of mammals, on top of which new information is popping up all the time to throw spanners in the works. Rather than trying to weigh up the recent academic literature myself (which is never really wise for a layperson), in what follows I will leave it to the experts (i.e. a well-respected and recent university-level textbook (1)).

With that proviso in mind, let’s begin at the beginning. When did mammals first appear? There are a range of figures out there. All of them, though, are way beyond 60 MYA. They’re actually in the region of about 205 to 225 MYA. Far from arising when dinosaurs became extinct (which, to be precise, occurred about 66 MYA)(2), it’s actually more accurate to say the opposite—that mammals and dinosaurs both appeared at similar times! (3)

The range of dates for the first appearance of mammals wafting around seem to be just as much a result of different definitions of mammals as anything else. I’m sure no-one reading this will want to get bogged down in semantics for the sake of a few million years, so I’m just going to take one of the common definitions of mammals—the group of animals known scientifically as Mammalia. This group first appeared about 205 to 210 MYA and is quite easy to define. It’s the common ancestor of all living mammals and all descendants of that common ancestor. In other words, it’s all living mammals, along with all those animals in the same family tree that have become extinct.

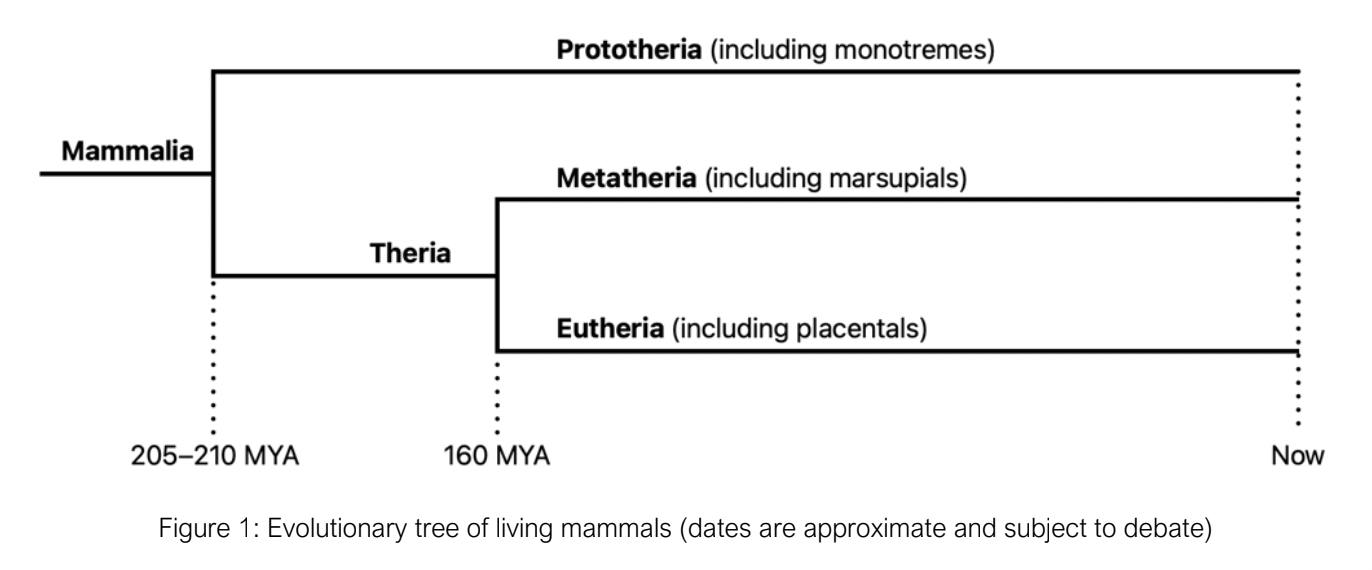

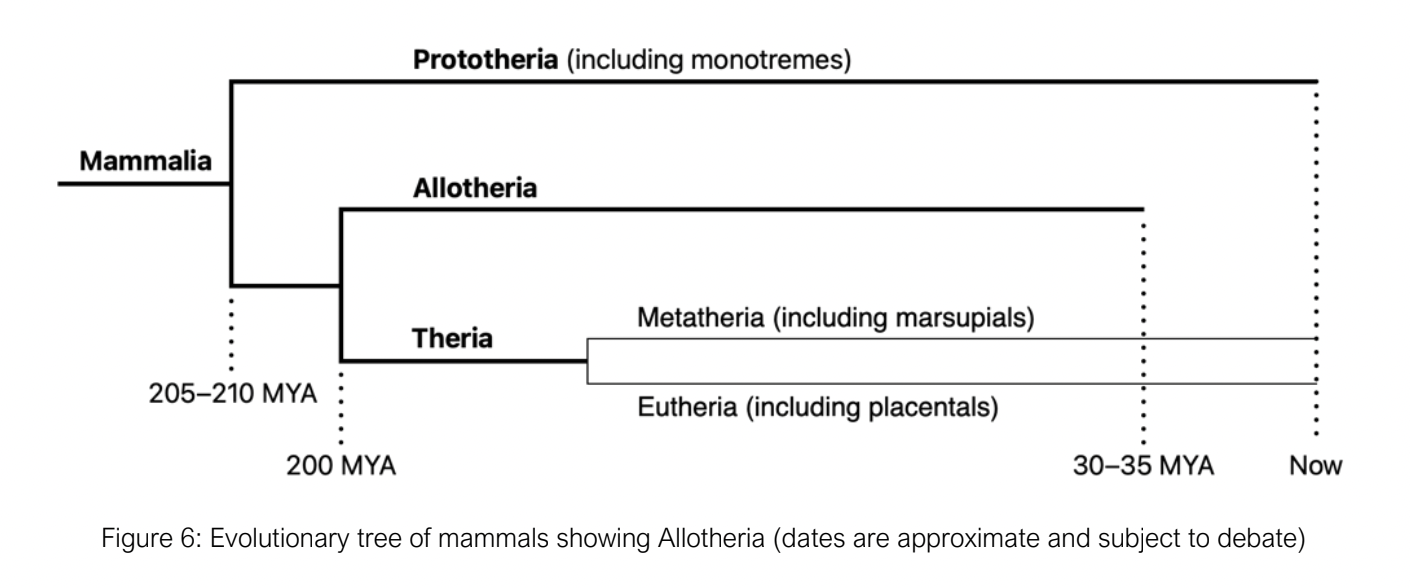

Figure 1 shows a basic evolutionary diagram for mammals (i.e. Mammalia). Living mammals fall into two main groups: Prototheria and Theria, with Theria being split further into Methatheria and Eutheria. The living members of each of these groups are:

- Prototheria: Monotremes (egg laying mammals), i.e. echidnas and the platypus (see Figure 2).

- Metatheria: Marsupials (mammals with pouches for young), e.g. kangaroos and koalas (see Figure 3).

- Eutheria: Placentals (4), i.e. all other living mammals, e.g. rats, cows, bears, dolphins, humans… (see Figure 4).

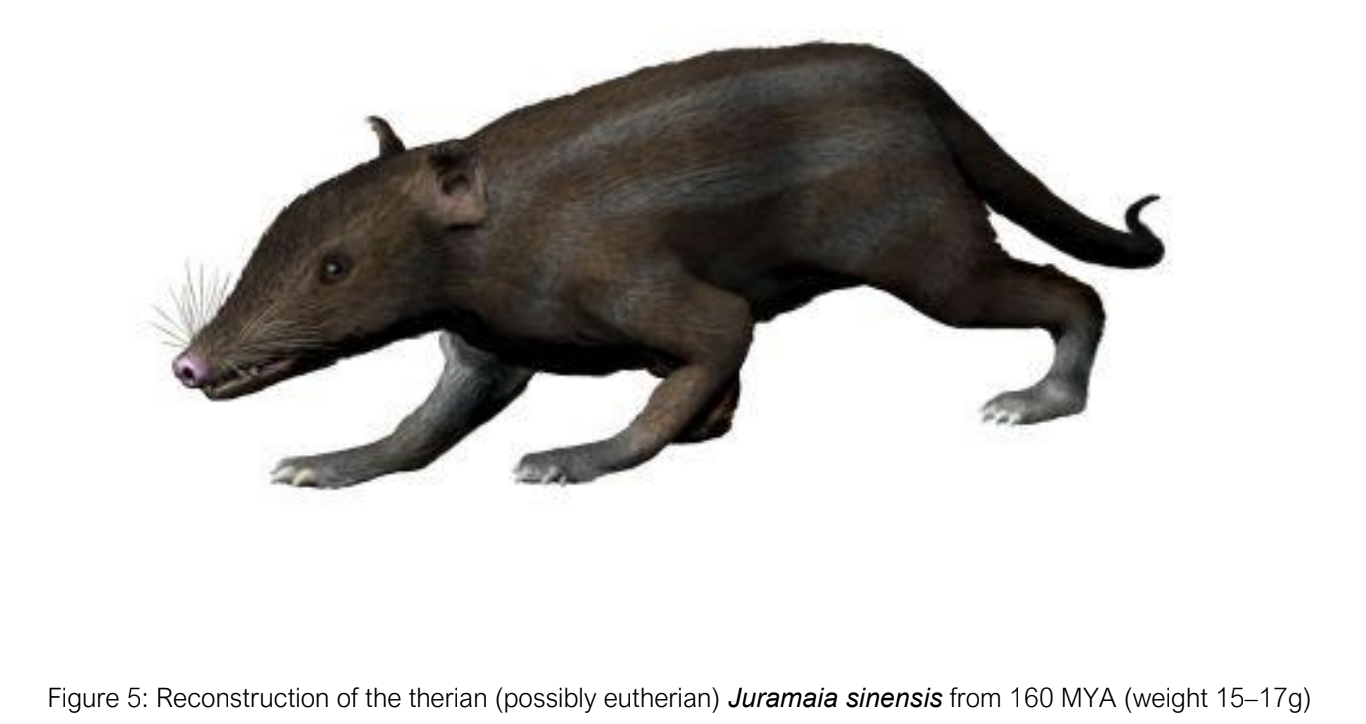

Although it goes without saying there is considerable debate about when each of these separate groups originated, it is generally agreed that they all predate the extinction of dinosaurs by at least several tens of millions of years (see Figure 1). So where did this common misperception about mammals only evolving after the extinction of dinosaurs come from? Well, it arose because of what happened after the dinosaurs became extinct. When dinosaurs were around, they ruled the world. There were big ones and small ones, occupying all manner of niches. This would have made it pretty difficult for any other animal to find a place to live—except… Dinosaurs were mostly daytime creatures. The night-time was generally free of those pesky dinosaurs, especially if you were going to be very small and crawl around quickly. So that’s what early mammals did. They were generally small nocturnal, shrew-like creatures (see Figure 5)(5). Even by the time dinosaurs became extinct, mammals hadn’t become any bigger than the size of a badger (6). But when the dinosaurs did become extinct… It was party time! Suddenly there were loads of free niches, especially in the daytime. Although many mammals also died off with the dinosaurs (7), there were still plenty around to party. Those that remained quickly evolved to exploit the new niches left by the dinosaurs. Having said that, some mammals were better party animals than others. Monotremes stayed in their own quiet corner and carried on much as before. They’ve never amounted to much. Metatherians (marsupials) had a bit of a party. But it was the eutherians (placentals) who were the real party animals. Placentals really took off after the extinction of the dinosaurs and diversified into many different groups. And this is where the idea that mammals only evolved after the extinction of dinosaurs comes from. It was only after the extinction of the dinosaurs that mammals (i.e. placentals) really began to take on the shape, size and forms that we are familiar with today. It was only once the dinosaurs disappeared that mammals (i.e. placentals) could rise to rule the world as they do today.

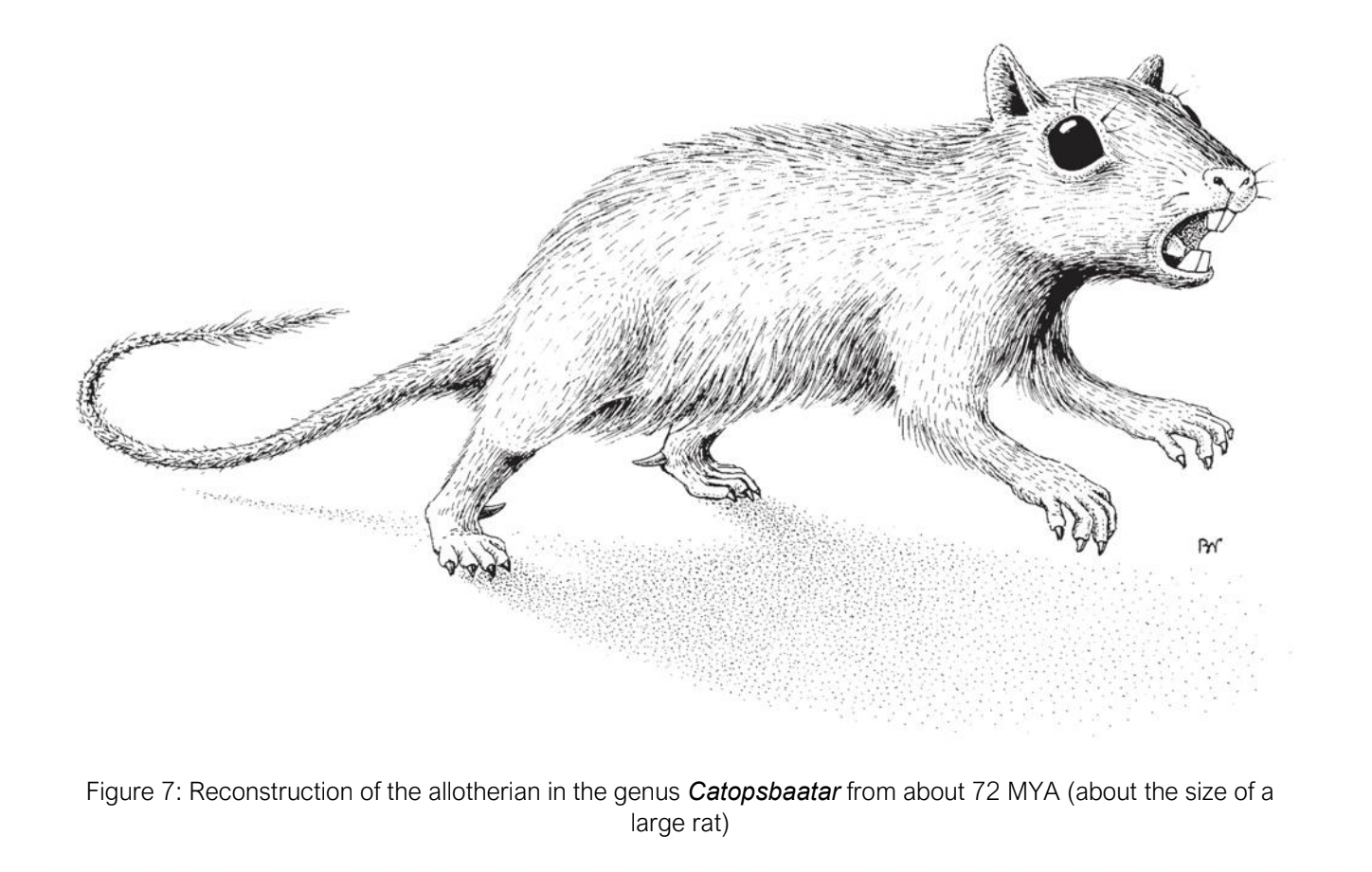

So that’s the evolutionary story of mammals living today in (very) brief. In order to talk about New Zealand’s past though, there’s a bit missing. Once upon a time there was a successful and wide-spread mammalian lineage sitting between Prototheria and Theria called Allotheria (see Figures 6 and 7). This lineage suffered badly in the mass extinction event that killed off the dinosaurs. The remaining allotherians managed to party a bit afterwards, but in the end they were probably outcompeted by placentals, and they became extinct by about 30 to 35 MYA. But that’s not all. Allotheria wasn’t the only mammalian lineage sitting between Prototheria and Theria. There were, in fact, many more mammalian lineages sitting between the two that have long since become extinct (imagine a diagram like Figure 6, but with lots of branches in it). It’s just that Allotheria is probably the most well-known. Since I’m not being particularly formal, I’m going to call all the lineages between Prototheria and Theria, “Allotheria (and whānau)”. (Please don’t tell any evolutionary biologist I’ve just written that.)(8)

In summary, mammals have been around for hundreds of millions of years. Up until the extinction of the dinosaurs most were very small, and none were big. Mammals divided into the extant groups prototherians (including monotremes), metatherians (including marsupials) and eutherians (including placentals) long before the extinction of the dinosaurs. After dinosaurs became extinct one group in particular took off, diversified and took over—and that is the placentals. Prior to the extinction of the dinosaurs there were also many other mammalian lineages as well (which I’m calling “Allotheria (and whānau)”), some of which were quite successful in their time. However they have long since become extinct.

Mammals in Australia

With that global picture in place, let’s have a quick look at the story of mammals in Australia. As noted already, this will give the background for the New Zealand story in the next article. The Australian story can be summarised under the headings of the main mammalian groups.

- Prototheria (monotremes): These originated in the Australian region a very long time ago and have always been there.

- Allotheria (and whānau): There are a couple of fossils of these in Australia from about 120 MYA.

- Metatheria (marsupials): This one is interesting, because, although Australia is known for its marsupials, Australia is not where they originated. The oldest marsupial fossils are actually from North America. However it was in South America where marsupials first took off properly. From there they made their way to Australia. The earliest marsupial fossils in Australia are from about 55 MYA. How did marsupials get to Australia, you may well ask? As seen in Part One of this series of articles, at 55 MYA Australia was joined to Antarctica. What wasn’t shown in Part One was that at the time Antarctica was also joined at the tip to South America, or at least almost so. It seems, then, that sometime around 55 MYA marsupials travelled from South America, to Antarctica and then on to Australia (Antarctica was much warmer then and covered in forests).(9)

- Eutheria (placentals): There is single fossil in Australia from about 55 MYA that many claim is a placental. However this is not definitive. Definitive placental fossils don’t appear in Australia until much later. There is a fossil of a bat from 26 MYA. As with the marsupials, these bats probably originated in South America. When it comes to non-flying mammals in Australia, the first definitive placental fossils are from around only 4.5 MYA. These (rodents) originated from South East Asia. The reason it took so long for these mammals to get to Australia is that Australia and South East Asia used to be a long way apart. The two moved closer together over a period of millions of years, and it would seem it is only in the recent geological past that the two have been close enough for animals to jump from one to the other.

And that’s the Australian story. If you’ve made it up to this point, you might be putting two and two together and feeling somewhat perplexed. Why on earth aren’t there any native (non-flying) mammals in New Zealand? If mammals have been around for 200 or so million years, and they were in Australia when New Zealand was still part of Australia, why weren’t they in New Zealand when it broke away? Or perhaps they were? If so, whatever happened to them?

Tune in next time for the final episode of the story of mammals in New Zealand.

Footnotes:

- Vertebrate Life (11th edition) by Pough et al.

- And to be further precise, we’re talking here about non-avian dinosaurs, i.e. dinosaurs that are not birds. Birds are actually dinosaurs, although most people aren’t aware of that. But that’s a story for another article…

- Dinosaurs first appeared about 230 to 245 MYA.

- As the name suggests, during gestation placentals attach to the mother via a placenta. However, marsupials also have placentas. What is different is that a marsupial placenta is generally less well-developed than a placental’s. A marsupial also has a very short gestation period and its placenta is only present for about 20% of that time. Conversely, a placental has a comparatively long gestation time and the placenta is present for most of it.

- This explains the exceptional sense of smell and hearing most mammals have today (humans, and related primates, have a very poor sense of smell compared with most mammals), not to mention good night vision. Incidentally, even today most mammals are small and nocturnal.

- This was Repenomamus giganticus from about 125 MYA.

- There has been much debate about what caused this general mass extinction. There is no doubt an asteroid hit the earth 66 MYA and caused major devastation. Did this cause the mass extinction? The best answer is probably that it was the final straw in a period in earth’s history when life as a whole was under considerable strain. This strain was possibly caused by prolonged and intense volcanic activity.

- Who made that label bold?

- Incidentally, monotreme fossils have been found in South America, so there was clearly two-way traffic of mammals between South America and Australia via Antarctica. Also incidentally, before humans arrived in Australia about 40,000 to 50,000 years ago there were many more species of marsupials there than there are now, including marsupial lions and giant kangaroos.

References:

Gibbs, G. 2016. Ghost of Gondwana: The History of Life in New Zealand (revised edition). Potter & Burton, Nelson. (pp. 72–74)

Lomolino, M.V., Riddle, B.R. & Whittaker, R.J. 2018. Biogeography: Biological Diversity across Space and Time (5th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA. (pp. 247–249)

Pough, F.H, Bemis, W.E, McGuire, B. & Janis, C.M. 2023. Vertebrate Life (11th ed.). Sinauer Associates, New York. (p. 233–234, Chapters 22 & 23)

Thomsen, T. 2021. The Lonely Islands: The evolutionary phenomenon that is New Zealand. Reed New Holland Publishers. (pp. 94–96, 194–196)

Picture credits:

- Figure 1: My own work, after Figures 22.1 and 23.2 in Vertebrate Life (11th edition) by Pough et al.

- Figure 2: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/1a/Duck-billed_platypus_%28Ornithorhynchus_anatinus%29_Scottsdale.jpg (Wikipedia, shared through Creative Commons licensing).

- Figure 3: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/49/Koala_climbing_tree.jpg (Wikipedia, shared through Creative Commons licensing).

- Figure 4: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e4/Suricata_suricatta_-_meerkat_-_suracte_-_Erdm%C3%A4nnchen_07.jpg and https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/6f/Rowan_Atkinson_and_Manneken_Pis.jpg (Wikipedia, shared through Creative Commons licensing).

- Figure 5: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juramaia#/media/File:Juramaia_NT.jpg (Wikipedia, shared through Creative Commons licensing).

- Figure 6: My own work, after Figure 22.1 in Vertebrate Life (11th edition) by Pough et al.

- Figure 7: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4c/Catopsbaatar.jpg (Wikipedia, shared through Creative Commons licensing).

It’s Time for Ewe to Go

It's time for ewe to go

It's time for ewe to go

Author: Ray Walter, last lighthouse keeper and first Tiritiri Matangi Island Ranger

From the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Archives: Bulleting 51, Spring 2002

As part of the revegetation of the south eastern paddock, it has been necessary to reduce the number of sheep. Approximately 60 sheep had been retained to keep the grass down until we were ready to replant the area.

It has been decided to keep a few sheep to graze the area between the lighthouse and the foghorn. Eventually, even these will go and all fences will be removed.

Mammals (Part 1): New Zealand’s Isolation from Gondwana

Mammals (Part 1): New Zealand's Isolation from Gondwana

Mammals (Part 1): New Zealand's Isolation from Gondwana

Author: Malcolm Pullan, Guide

Date: October 2024

As a guide, one of the first things I tell international visitors to Tiritiri Matangi is that New Zealand has no native land mammals apart from bats. I suspect many other guides do the same. It certainly is quite an unusual fact and accounts for so much of why New Zealand bird life (and indeed all New Zealand life) is the way it is. I wonder how many guides go on to explain the absence of land mammals by some variation of the statement that New Zealand broke away from the rest of the world about 60 MYA (million years ago) before mammals evolved? I know I did when I first started guiding. It was one of those statements that I sort of grew up with and didn’t think to question. I wasn’t guiding for long though before I did begin to wonder how true that statement really was, and so I began to dig a little deeper. It turns out there are several things wrong with the crude statement: “New Zealand broke away from the rest of the world about 60 MYA before mammals evolved.” The truth—or at least the best current guess at the truth (because science is always evolving as new facts come to light)—is even more fascinating.

This article and the next two give a summary of the latest thinking on the story of mammals in New Zealand. This story goes under three headings:

- When did New Zealand really break away from rest of the world?

- When did mammals really evolve?

- Were there ever mammals in New Zealand before humans arrived (other than bats)?

This article begins the story by answering the first question. This is more of a question in geology and not really related to mammals explicitly. Nevertheless, it is necessary background information on which to overlay the answer to (2). I also think it’s rather an interesting question in its own right.

Before I begin with the first question, here are the short answers to all of them:

- About 80 MYA.

- About 205 to 210 MYA.

- Yes!

Intrigued? Read on…

When did New Zealand really break away from the rest of the world?

The first question here is, who wants to know? Most of the time the answer to when New Zealand broke away from the rest of the world is given by geologists, while much of the time the question is asked by people interested in plants and animals, i.e. people with an interest in biology. The end result is confusion, because the two groups of people are often talking about two different things. If you’re thinking about plants and animals, it’s rather fundamental to know whether they are on dry land or under water. Thus when biologists want to know when New Zealand broke away from the rest of the world, they want to know when there was some water between the two landmasses. Sounds obvious, doesn’t it?

Well, not to a geologist! You see, geologists tend to talk about rocks more often than water. When they talk about landmasses being separate, they often mean the underlying rocks of the two landmasses are separate rather than just being separated by sea. The difference here is that it is possible for underlying rocks of two dry landmasses to be joined even when there is no dry land joining them. When underlying rocks of two separate dry landmasses are joined, geologists often say the two landmasses themselves are joined, whereas biologists would say they aren’t. The North and South Islands are good examples here, as is Great Britain and the European continent. Both these pairs of landmasses share common underlying rocks, yet both have sea separating them.

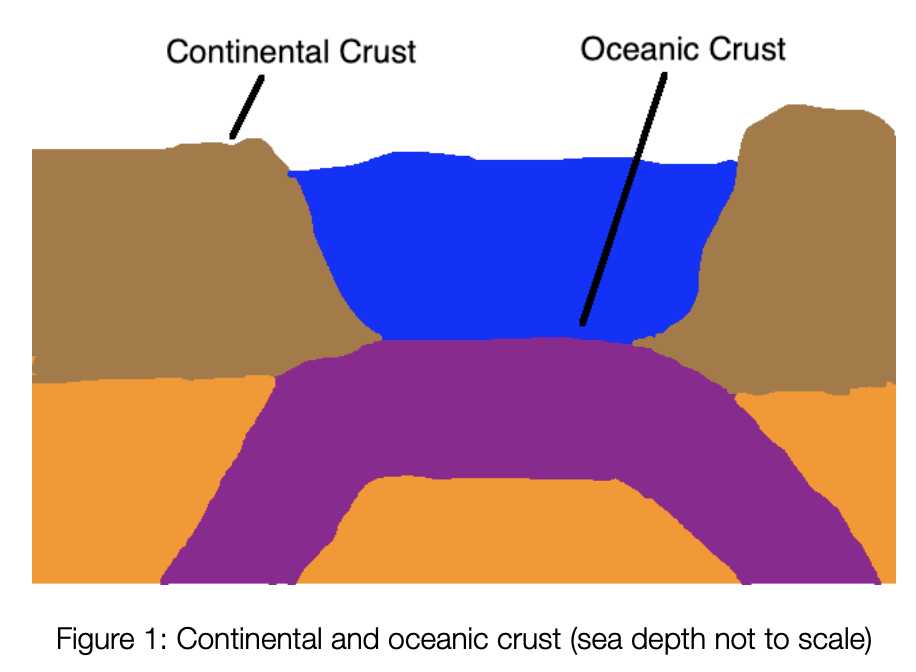

Are geologists just trying to be annoying and confuse everybody? Not at all. They are simply distinguishing between the two fundamental types of earth’s crust. The earth’s crust, i.e. the outer layer of the earth, is composed of two fundamentally different types of crust: oceanic crust and continental crust. Oceanic crust forms the bottom of the deep oceans and is generally at a depth of around 4km under the surface (but can be up to 11km in trenches). Continental crust forms the large landmasses of the earth including where these landmasses slope down to meet the oceanic crust at depth under the sea (see Figure 1). When geologists say two landmasses are separate, they tend to mean there is oceanic crust between them. One implication of this is that there is sea at a depth of around 4km or more between the two landmasses. This is quite different from saying there is no sea between the pieces of land at all! The reason geologists tend to talk about landmasses as pieces separated by oceanic crust, rather than pieces separated by sea, is that each piece of continental crust behaves as a unit, i.e. it changes and moves around as a segment of the earth’s crust independently of where the sea happens to be at any one time.

What’s all this got to do with when New Zealand broke away from the rest of the world? Well, that rough figure of 60 million years for when this occurred is actually more of a geologist’s answer. It’s roughly the time when the continental crust of New Zealand became properly separated from any other piece of continental crust and there was oceanic crust completely surrounding New Zealand. But there would have been an awful lot of sea between New Zealand and any other landmass then—an awful lot of sea that land animals wouldn’t have been able to cross for quite some time before this.

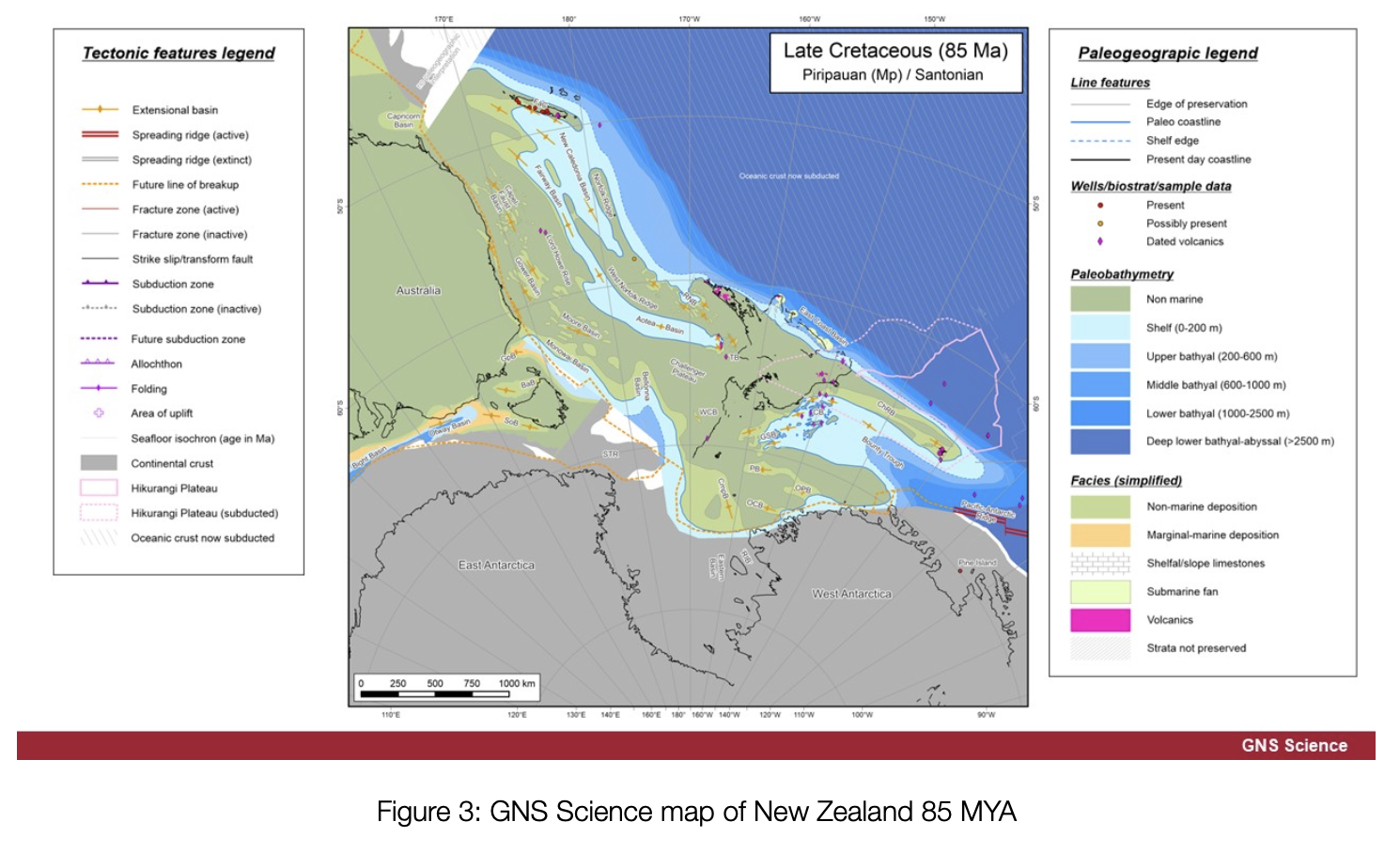

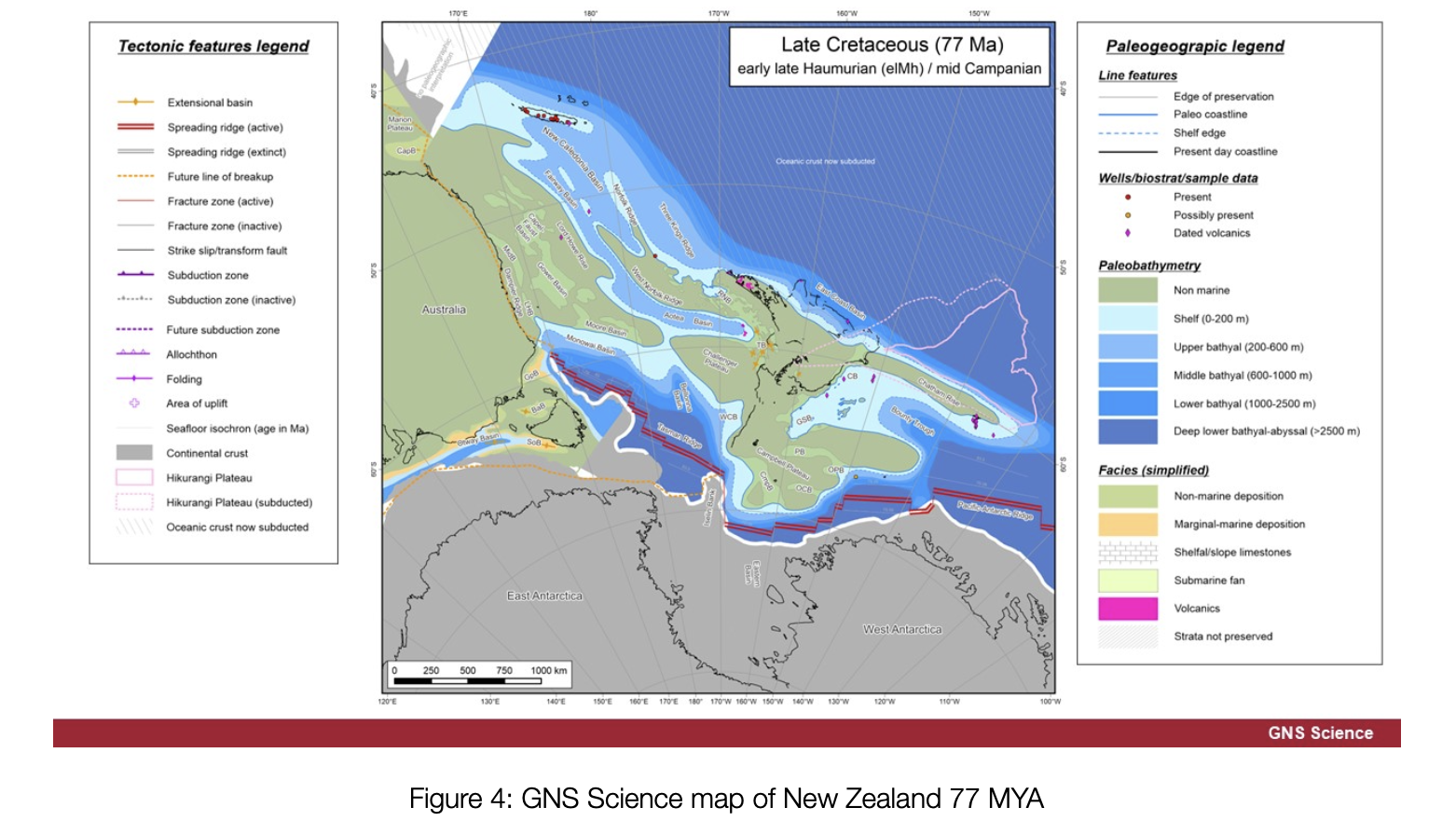

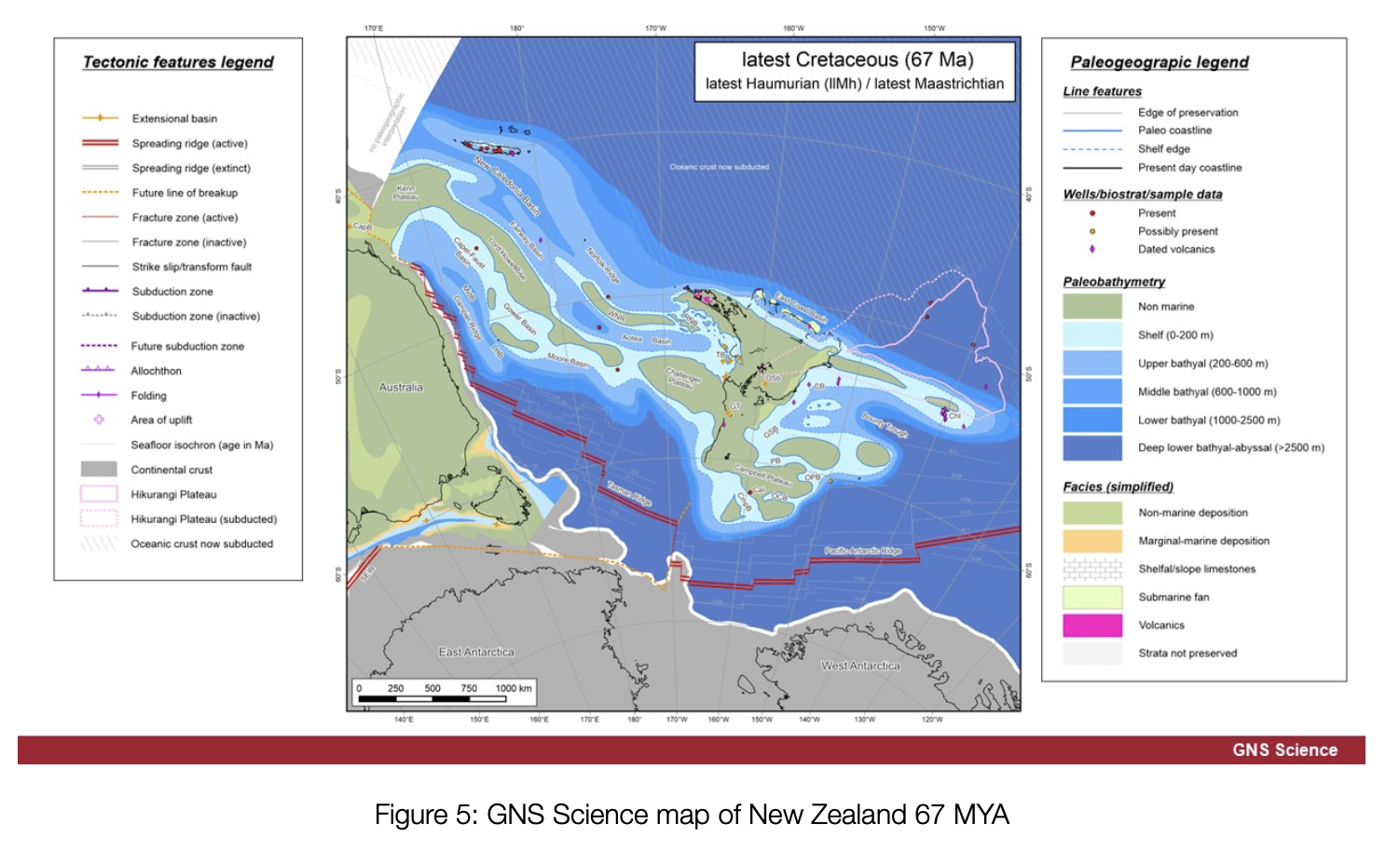

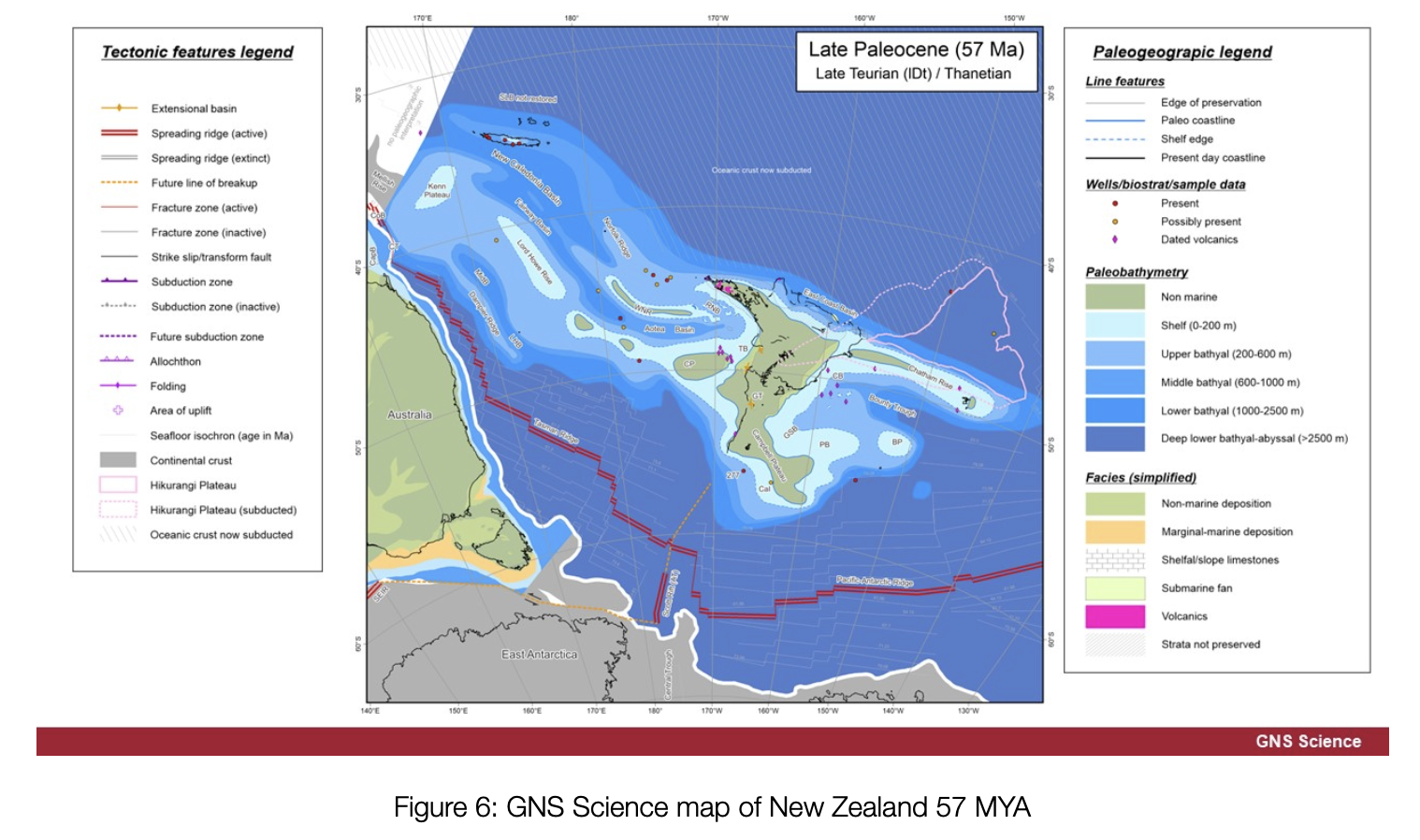

So what is the answer for biologists? When was there water between New Zealand and the rest of the world? The short answer is given above, i.e. about 80 MYA. To explain this, i.e. to reconcile the two answers, we need to return to geology for the story of the formation of New Zealand. The outline of this story has been known for a few decades now. In 2022, though, GNS Science released a series of fifteen maps showing New Zealand’s formation from 98 MYA ago to the present day (1). These maps give a much clearer picture than ever before of the story of New Zealand’s formation. A summary of this story is as follows (see Figures 3–6 for a selection of the GNS Science maps illustrating this story—and see the footnotes for examples of the processes described operating in today’s world if you’re interested): (2)

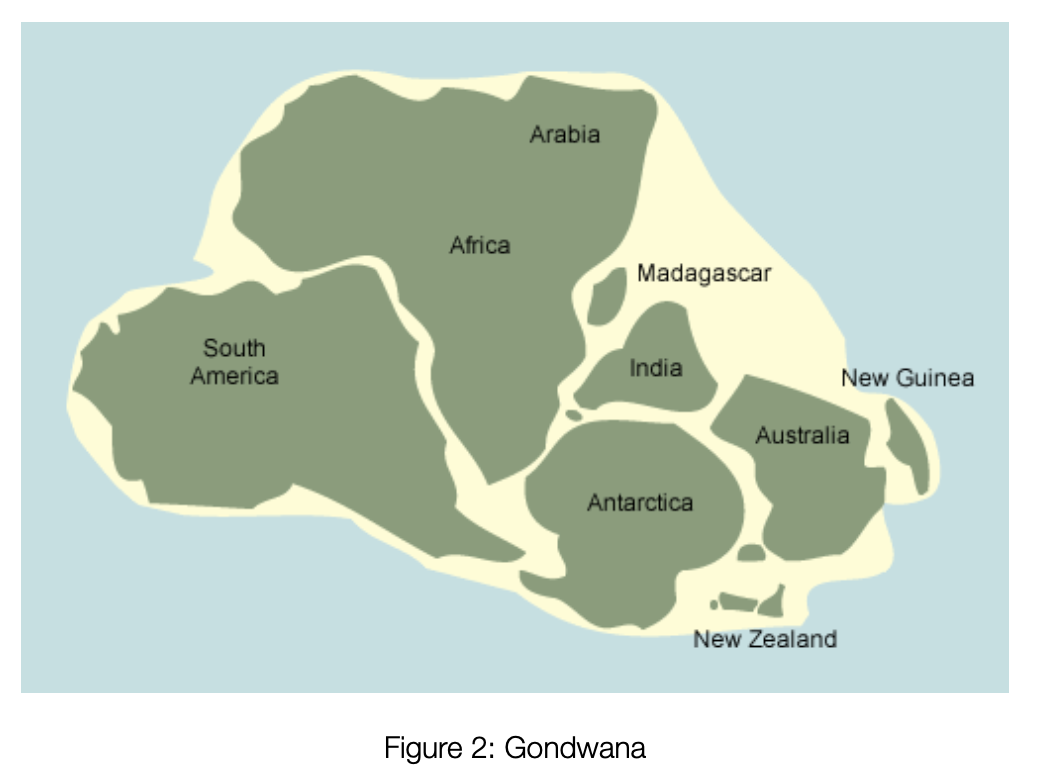

- About 180 MYA there was a supercontinent called Gondwana (see Figure 2). It comprised the land that is now India and the continents of the southern hemisphere (including Antarctica).

- By about 105 MYA Gondwana had broken up into various pieces, but New Zealand, Australia and Antarctica were still joined together.

- A rift began to form from this time separating New Zealand from the combined continent of Australia and Antarctica. As the rift formed, the land around it stretched and sank. (3)

- Sea began to appear in the rift soon after it formed. (4)

- The rift worked like a zip, unzipping New Zealand from Antarctica first and then working its way up towards and then along the coast of Australia.

- Oceanic crust began to appear in the rift about 85 MYA. (5)

- Sea completely surrounded New Zealand by about 80 MYA.

- The continental crust that New Zealand sits on (6) became completely isolated from the continental crust of Australia and Antarctica about 60 MYA. (7)

- Oceanic crust continued to form between the two pieces of continental crust until about 55 MYA. (8)

So when did New Zealand break away from the remnants of Gondwana? Well, to be precise, it’s a story spread over many millions of years. If one really needs to put a single date on it though, a geologist might want to say about 60 MYA, being the time New Zealand was surrounded by oceanic crust. Alternatively, a geologist might want to say about 85 MYA for when oceanic crust first appeared. If, however, one is interested in New Zealand life (which includes most Tiritiri Matangi people),

then the best figure is probably about 80 MYA for when New Zealand was completely surrounded by sea.

So there you have it—the first piece of the puzzle in the story of mammals in New Zealand. Part two of this series will give a brief summary of the evolution of mammals globally, with an emphasis on the story of mammals in Australia. Given that New Zealand is a chip off the Australian (and Antarctic) block, the Australian story forms the opening chapter of the story of mammals in New Zealand.

Footnotes:

(1) These maps can be downloaded and a video of the map sequence can be found here: https://www.gns.cri.nz/data-and-resources/the-100-million-year-history-of-te-riu-a-maui-zealandia-in-maps/.

(2) Several relatively recent sources give dates for the events described, such as Mortimer and Cambell’s Zealandia and Gibbs’ Ghosts of Gondwana. Most of the dates given above come from the former source. Where possible, I have estimated other dates from the more recent pictures by GNS Science, e.g. the date of 80 MYA for New Zealand being completely surrounded by sea.

(3) A contemporary example of a rift forming in a continent is the Great Rift Valley of east Africa that runs through countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Ethiopia. If this rift continues, east Africa will eventually separate from the rest of Africa like New Zealand has from Australia and Antarctica.

(4) The Red Sea is a more contemporary example of sea flooding into a continental rift. In fact, the Red Sea is part of the rift forming the Great Rift Valley in Africa (see previous footnote).

(5) Oceanic crust has appeared in the Red Sea (see previous footnote).

(6) This piece of continental crust is called Zealandia. In addition to New Zealand, it includes other pieces of dry land, such as the distant Chatham Islands, the sub-Antarctic islands, and even Norfolk Island and New Caledonia.

(7) Madagascar is similar to New Zealand in that it split from remnants of Gondwana and is now completely surrounded by oceanic crust.

(8) Oceanic crust continues to be formed today in rifts formed a very long time ago. One of the most well-known examples is the Mid-Atlantic Ridge that runs all the way down the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. The oceanic crust being formed there widens the Atlantic Ocean by about 2–5cm per year.

References:

Gibbs, G. 2016. Ghost of Gondwana: The History of Life in New Zealand (revised edition). Potter & Burton, Nelson. (Chapter 4)

Lomolino, M.V., Riddle, B.R. & Whittaker, R.J. 2018. Biogeography: Biological Diversity across Space and Time (5th ed.). Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA. (pp. 250–254, 258)

Mortimer, N., Campbell, H. 2014. Zealandia: Our Continent Revealed. Penguin Books, Auckland. (pp. 202–204)

Pough, F.H, Bemis, W.E, McGuire, B. & Janis, C.M. 2023. Vertebrate Life (11th ed.). Sinauer Associates, New York. (p. 492)

Wicander, R. & Monroe, J.S. 2016. Historical Geology: Evolution of Earth & Life Through Time 8th ed.). Engage Learning, Boston. (p. 50)

Picture credits:

- Figure 1: My own work (can you tell?!)

- Figure 2: Zealandia website: https://www.visitzealandia.com/About/History/The-Continent-of-Zealandia (slightly modified).

- Figures 3–6: https://www.gns.cri.nz/assets/15-Maps-of-Zealandias-History.zip. The original source of the maps is:

Strogen, D. P., Seebeck, H., Hines, B. R., Bland, K. J., & Crampton, J. S. 2022. Palaeogeographic evolution of Zealandia: mid-Cretaceous to present. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics, 66(3), pp. 528–557. (https://doi.org/10.1080/00288306.2022.2115520)

Argentine Ants on Tiritiri Matangi

Argentine Ant

Argentine Ant

Author: Chris Green, Department of Conservation

Date: From the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Archives, Dawn ChorusHeader photo: Chris Green

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Archives, Dawn Chorus, Autumn 2000

Ten years ago a new immigrant species slipped quietly into New Zealand, arriving in Auckland and establishing itself in Onehunga, just prior to the Commonwealth Games in 1990. That immigrant was the Argentine ant (linepithema humile) and initial surveys quickly revealed it to be quiet widespread. It was decided that there would be no welcoming committee dishing out pesticide sprays, or free food laced with insecticide, as has been the scenario when insect pests such as fruit fly or tussock moth arrived. Those entomologists “in the know” however, knew that New Zealand had come of age with this arrival of one of the world’s most invasive pest ant species.

The Argentine ant is a native of South America and has been invading overseas countries, including North America, Hawaii, South Africa, and Australia, for more than 50 years. Since its arrival in New Zealand, Argentine ant has spread to many areas in the Auckland Region, established itself in Tauranga and Morrinsville, and has recently been reported from Christchurch, Gisbourne and west of Dargaville. Now it has been found on Tiritiri.

Argentine ants are small-two to three millimetres long-are a pale red-brown and cannot spread by flying, only by walking or being carried. The ant is particularly successful because it develops large multi-nest colonies with huge numbers of workers that swamp food sources. Like most other ants they feed on sweet, surgery solutions such as nectar, as well as protein-based foods such as insects. Overseas research has shown that after these ants invade a site most other ant species disappear, any many other insect groups suffer a significant decline.

Argentine ant has several attributes that make it much more successful than other ants. A key feature that sets the species apart from most other ant species is that workers from neighbouring Argentine ant colonies cooperate with each other. Thus when a new food source is located, such as a tree coming into flower, all surrounding nests will be able to partake. Because it is very active, fast-moving ant, the species often locate new food sources ahead of other species and can thus more efficiently dominate all available sources in the area occupied. The species also features a highly developed chemical defence secretion, which will force the retreat of most other ants and invertebrates, even when these other species are much larger than Argentine ants. Thus despite their small size, Argentine ants often frequently win one-on-one contests.

Unlike virtually any other ants in New Zealand, Argentine ant trails feature huge number of ants, moving in a stream of up to five to six ants wide, like a busy six-lane motorway. These huge trails can be seen frequently moving up trunks of flowering trees, where the ants feed on nectar from flowers. They are also well known to exploit or “farm” honeydrew from other insects such as the mealybugs, which are common on flax Tiritiri. The sheet numerical superiority of the species tends to lock up these food resources and prevent other fauna feeding on them. This has implications for many species of invertebrates, lizards and birds that would normally feed on nectar and honeydew. As well as being extremely successful competitors the ants are predators of many invertebrate groups and there are even reports of them killing recently hatched chickens and invading broken eggs.

With an international reputation like this, it is a species that the Department of Conservation would prefer not to see in our nature reserves, especially our offshore islands used as safe havens for endangered species. Therefore, several years ago I put up a bid to have research undertaken in Auckland to determine if Argentine ant is likely to have such a severe impact on our native ecosystem as has been reported overseas. As a result two studies were instigated in Auckland last year, one by Landcare Research Ltd, and another by a PhD student. Results of this research will be some years away, but in the interim the decision has been made by the Auckland Conservator that the any should be eradicated from Tiritiri.

The Landcare contact includes research on a new insecticide ant bait, and early trials elsewhere in Auckland indicate it is very effective against the ant. Landcare has agreed to take part in an eradication campaign using the bait.

Surveys carried our over April indicate that the ant is present over about 5% of the island, centred on the wharf area. It is fortuitous that it has not reached the nursery or buildings at the top of the island, and special precautions are being taken to reduce the risk of the ant being carried up there. Other areas of the island are still being checked in detail.

It is extremely important that the ants are left undisturbed so they do not spread out even further before poisoning over the winter period. If visitors to the island see any ants please do not touch them. When disturbed, the multi-queened nests are likely to fragment, and potentially each queen can set up a new separate nest, thus spreading the problem over a greater area.

It appears as though Argentine ant has been on Tiritiri for some time, possibly several years. The best guess is that is that is probably came in on heavy machinery as a complete nest. The Department if moving quickly to eradicate the species as soon as possible.

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Archives, Dawn Chorus, February 2005

Argentine ants were first discovered on Tiritiri in March 2000. The species is recognised as one of the 100 most important pests of the world due to the impact it has on other wildlife, particularly invertebrates, but also lizards, frogs and birds. The ant has many attributes which make it such a successful pest (see Bulletin f or details) but three key features stand out. Each nest can have huge numbers, up to hundreds of thousands, foragers are active 24 hours a day, unlike most ants which are either diurnal or nocturnal (not both), and all Argentine ant nests co-operate with each other. These, and other features, mean the species can dominate whole ecosystems where conditions are suitable.

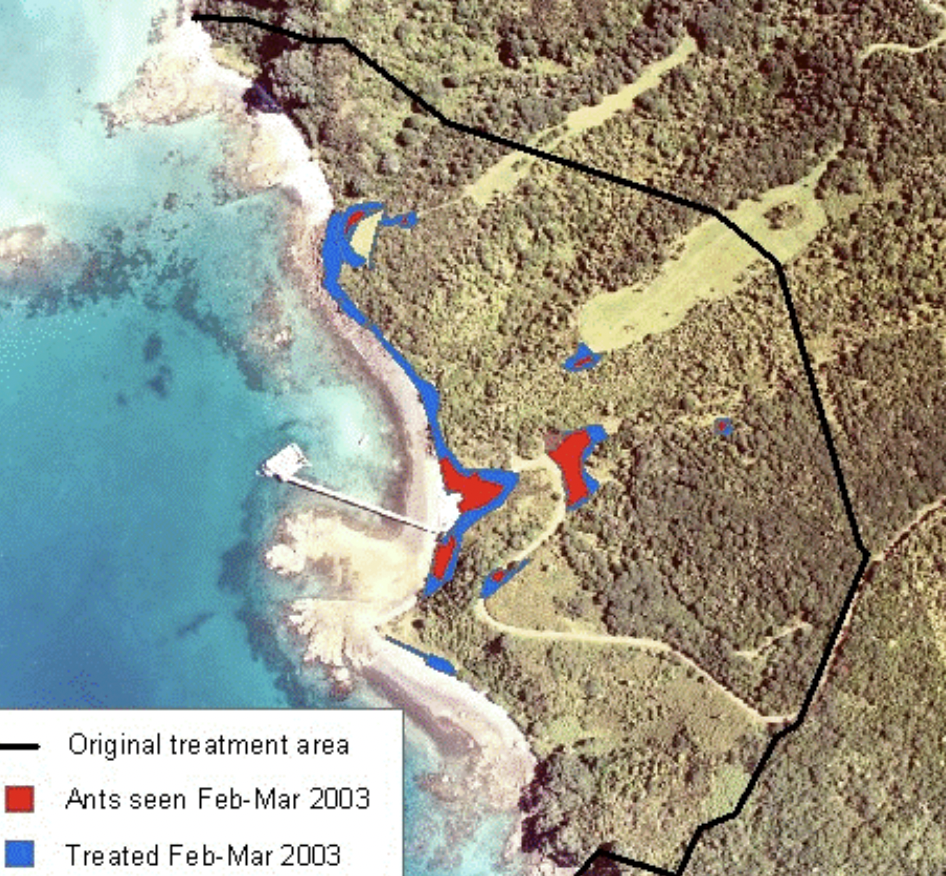

During the summer of 2001 a group of 14 ant specialists and volunteers f rom around New Zealand assembled on Tiritiri to administer the first treatment of poison baits over the whole 11 hectare area mostly centred around the wharf but also including a small population at Northeast Bay. Insecticide paste baits were placed every 2 – 3 metres in a grid fashion, as described in Bulletin 45. Intensive post-bait monitoring revealed that a massive 99% of the ants were killed. No longer were swarms of ants seen on trees and concrete edges by visitors waiting f or the afternoon ferry.

Following on from that first treatment a second treatment was applied in December 2001, again covering the entire previously infested area. As in the first season, there was a good kill but, frustratingly, once again a small number survived. However, there was no sign of any at Northeast Bay. In fact there hasn’t been an Argentine ants seen there since autumn 2001. Yeah!!!

During the 2002-03 season, with the assistance of Landcare Research, there was a lot of research into monitoring methods to detect small nests of surviving ants. Sticky traps, pitfall traps and various non-toxic baits were trialled. In the end we chose non-toxic baits placed in tubes with netting covers to prevent interference from other wildlife. Monitoring from December 2002 through to February 2003 showed surviving colonies of Argentine ants at just eight sites (see red areas on photo). All of these were initially small colonies but two, around the wharf shelter and above the wharf pond, grew rapidly in size during summer with the ants covering about 300 square metres at each site by early March. All eight sites, plus buffer areas (blue areas on photo), were treated with insecticide baits during March – April. Compared to the large scale treatment of the whole 11 hectare area (inside the black line on photo) the spot treatment of these sites was straightforward. However, particular attention was paid to getting optimum weather conditions and ensuring there were no gaps in bait coverage. Each site was baited twice, a month apart. Intensive monitoring during January – March 2004 showed no surviving Argentine ants at any of the sites spot treated during 2003 so the attention to detail really paid off. Other sites were monitored and only two small nests were found. Both were spot treated twice, as per the previous season. Therefore, after four years of the eradication programme I feel we are very close to eradication but now the real grind starts. In any eradication programme the last individual is always the hardest and most expensive to kill. Making sure there are no survivors is the tricky part – that is the current challenge. Two years Argentine ant-free status is required before the programme can be declared successful. Argentine ant was first found in New Zealand in 1990 and is now widespread in many parts of Auckland, as well as some towns to the north and south. Thus we all need to be forever vigilant to ensure no new nests of Argentine ants are transported to Tiritiri. As with rodents and other pests, prevention is better than cure.

Aerial photo of main Argentine ant infestation showing entire area treated in years one and two (within the black line), ant sites for year three (red areas) and buffer areas (blue) treated in year three.

MinterEllisonRuddWatts (MERW), our primary corporate partners

MinterEllisonRuddWatts (MERW), our primary corporate partners

MinterEllisonRuddWatts (MERW), our primary corporate partners

Author: Debbie Marshall, Operations Manager

Date: September 2024Header photo: Jonathan Mower

MinterEllisonRuddWatts (MERW), are our primary corporate partners. Their stated purpose is “Working with you to help shape New Zealand’s future”. They are very involved with Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi (SoTM) under the auspices of their Community Investment Programme.

At the recent SoTM AGM, Stephanie de Groot, Partner; environment, planning and resource management, told members that “.. the pillars of our sustainability strategy are Environment, People and Practices. These focus on responsible consumption and production of goods and services, striving towards nett zero by 2050, being an inclusive and equitable place to work, doing what matters for their people and communities, and partnering with clients and others to tackle sustainability issues”.

Their legal team have looked at our procedures in terms of the Health & Safety Act 2015, the proposed accommodation facility and the concessions SoTM has with the Department of Conservation. They also offer support in areas of Human Resources, Finance, Marketing, Business Development and IT.

Since they joined up in June of 2023 most of their partners and staff have come to the motu, in groups of 10-12, working with our guides doing track trimming and cleaning up beaches and ditches or anything else that needs doing, working hard and happily regardless of the weather.

A recent visit took them to the northeast end of the island where the local takahe family were very taken with the goings on. They marched up and down checking out the piles being thrown into the bushes and staying nearby for the entire time the clean-up was happening.

The team’s appreciation of the clean, clear air and stunning environment was a reminder to the guides of how privileged we are to be able to showcase the island with a corporate sponsor who shares our values.

Flower feast week on Tiritiri Matangi as the island begins its spring flower display

Flower feast week on Tiritiri Matangi as the island begins its spring flower display

Flower feast week on Tiritiri Matangi as the island begins its spring flower display

Author: Jean Goldschmidt, guide

Date: 15th August 2024

Header image credit: Kay Milton

Flower feast week on Tiritiri Matangi as the island begins its spring flower display. Carpets of yellow cover the tracks under kowhai trees as the tūī rummage and attack each flower sending discarded petals to the ground. Too soon these delicious golden bell-like flowers will be gone leaving the ravaged trees to begin their cycle of regrowth once more.

The children in my group today do not hunt for the spectacular but are seeking the more modest flowers of Aotearoa, which they find hiding in the foliage. Our insect-pollinated flowers may be tiny but they are significant as the birds feed on their pollen and litter the ground with the carcasses.

As the only group walking up the road these exuberant, energetic ten-year-olds make the most of the freedom to leap ahead when they glimpse a bird, call out a name, listen for the call of the tieke or rush to the record sheet to check off their sighting. Standing still is impossible so any offering from me is brief. After the first experience with the magnifying glasses, they desire nothing else. Their fascination knows no bounds as they hold the glass to every leaf, feather, stalk, or stone.

Under a pūriri, flush with ruffled new dark green leaves they find the tree’s delicate mauve flowers. Through the glass the long stamens full of pollen hang out almost beyond the petals and look so beautiful I wish I were a bird and able to nuzzle in with my nose. But they find more in the tree. Looking up they point to tiny seeds in colours of white, pink, and finally the luscious red of the ripe berry. It is no wonder this is the Tiritiri Matangi supermarket tree.

Cream flowers drip from the māhoe and karamū but nothing can be more beautiful than the white flowers of the mānuka or the red of the karo peeping out from their delicate enclosures. Seen through the magnifying glasses these miniature flowers come to life, in a way that help us understand why the birds so love these flowers.

The children are on the hunt for the birds their teacher had taught them about and for which they know the Māori names – the hihi, a bird they have never seen and the kererū known to only a few. They quickly recognise the korimako, marking each sighting on the tally sheet until it overflows. Excitement mounts when a male hihi perches on a branch at eye level and remains in place long enough to be admired. Something was up with the pōpokatea. I have never heard such a racket. Are they defending territory or has a rival stolen their favourite female? Whatever it is there is anger from both sides of the track. In their large groups they usually fly across the path with their gentle swishing call. We leave the chaos hoping they can sort it out themselves.

Out came the glasses again and this time we look at the fine threads of the skeleton leaves, spiders and insects in the cabbage tree trunks and the multi-coloured lichens. After a brief explanation of the pūriri moth, the popular Māori father we have with us tells of how his grandfather extracted the pūriri grubs from holes in the tree and ate them, just like I did as a child eating huhu grubs found tucked in rotten wood. He remembers a peanut butter taste. He also told of his parents rubbing the kawakawa leaves into a pulp and having it applied to any cut, scratch or pain he had.

As we walk along one little girl asks how old I am. When I don’t respond she says, “I won’t tell anyone.” Then later still “Are you 100?”. “Nearly “, I say. She tried again at 92. They love the puppets and the best spotter spent his time at the back of the line. Then, thinking I could rid them of excess energy I race them up the track arriving at exactly 12.30, our deadline. At lunch, guides share their stories of the fun they have had with their groups as there is always something to enjoy and for me, there is always some new learning.

The tīeke/saddleback scheme and what it can teach us

Celebrating 40 years of tīeke/saddleback on Tiritiri Matangi

Celebrating 40 years of tīeke/saddleback on Tiritiri Matangi

Author: Kay Milton and John Stewart, Biodiversity Sub-Committee

Date: May 2024, Dawn Chorus 137

Header image credit: John Sibley

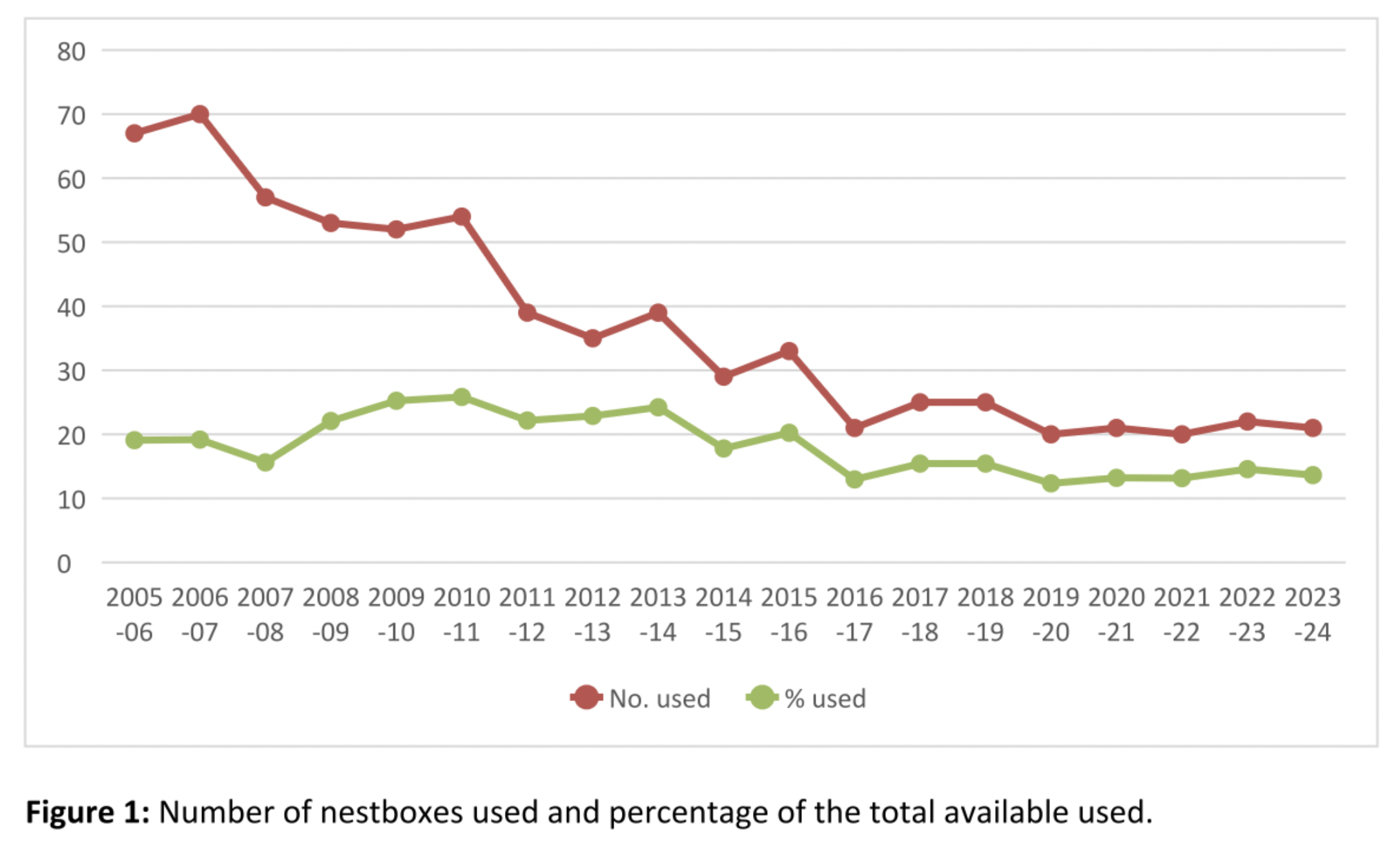

When tīeke/saddleback arrived on Tiritiri Matangi in 1984, it was truly the beginning of an era. Not only did they bring new sights and sounds to enrich the experience of anyone visiting the Island, they also marked the beginning of a project that would consume many working hours over the subsequent 40 years and which continues to this day. In 1984, only a small fraction of the original bush cover remained, and the planting programme was only just getting underway. This meant there were very few sites where tīeke could nest, so boxes were provided for this purpose. There were 360 boxes, but regularly monitoring this number proved difficult, and, as the bush planted between 1984 and 1994 has matured, an increasing number of ‘natural’ sites has become available. Between 2008 and 2012, the number of boxes was reduced to a level that could be more easily managed by a team of volunteers. Since then, it has been relatively stable at around 150-160 boxes.

Barbara was tasked with the responsibility of checking the boxes once a week during the season, and twice a week when eggs were hatching. This was quite a laborious task, which required a great deal of dedication, attention to detail, and physical exertion. Ray prepared dinner for them on the days when Barbara was occupied with checking the boxes. Barbara and Ray also used to band the tīeke chicks in the nest boxes.

Left image: Pulli 6 days old. Right image: Pulli 13 days old

Left image: Pulli 6 days old. Right image: Pulli 13 days old

Figure 1 shows that, over the past eight years, fewer than 30 boxes per season have been used by tīeke, indicating that a large majority of the birds are using natural sites. Why do we continue to provide nest boxes at all if there are plenty of other sites for the birds to use? Because, although the birds may no longer need them, they have continued to use a proportion of them each year and, in doing so, they provide us with a mechanism for observing their breeding behaviour and gauging their success. Ideally, to observe all the significant events in the life of a nest (building, lining, egg-laying, hatching, chick growth, and fledging), nest boxes should be checked every seven to ten days. This has been done consistently since 2010, with the exception of the two seasons between 2021 and 2023, when Covid restrictions and the pressure of other work made it impossible. The very welcome recruitment of eight new volunteers in 2023 has enabled regular monitoring to be resumed.

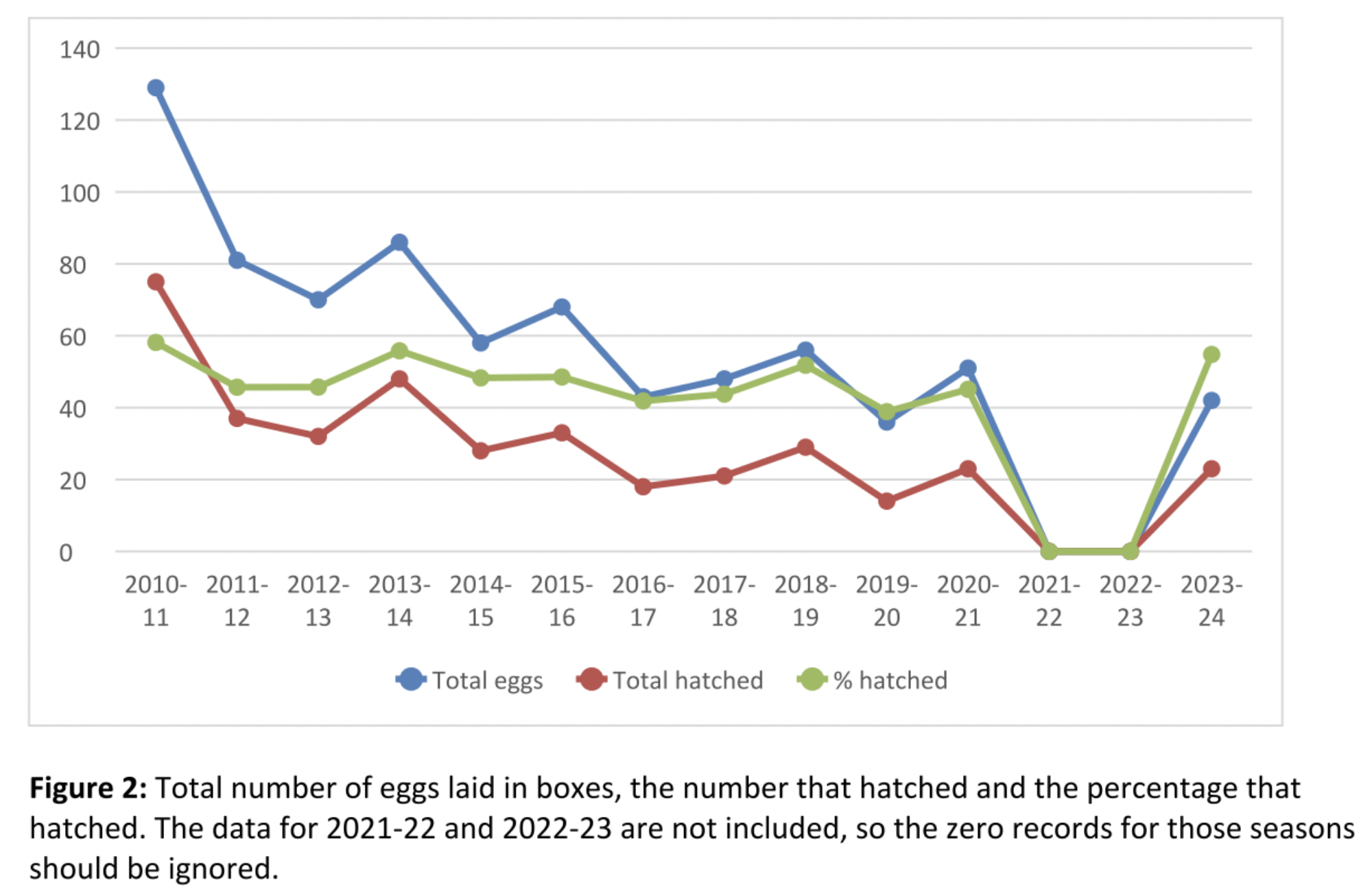

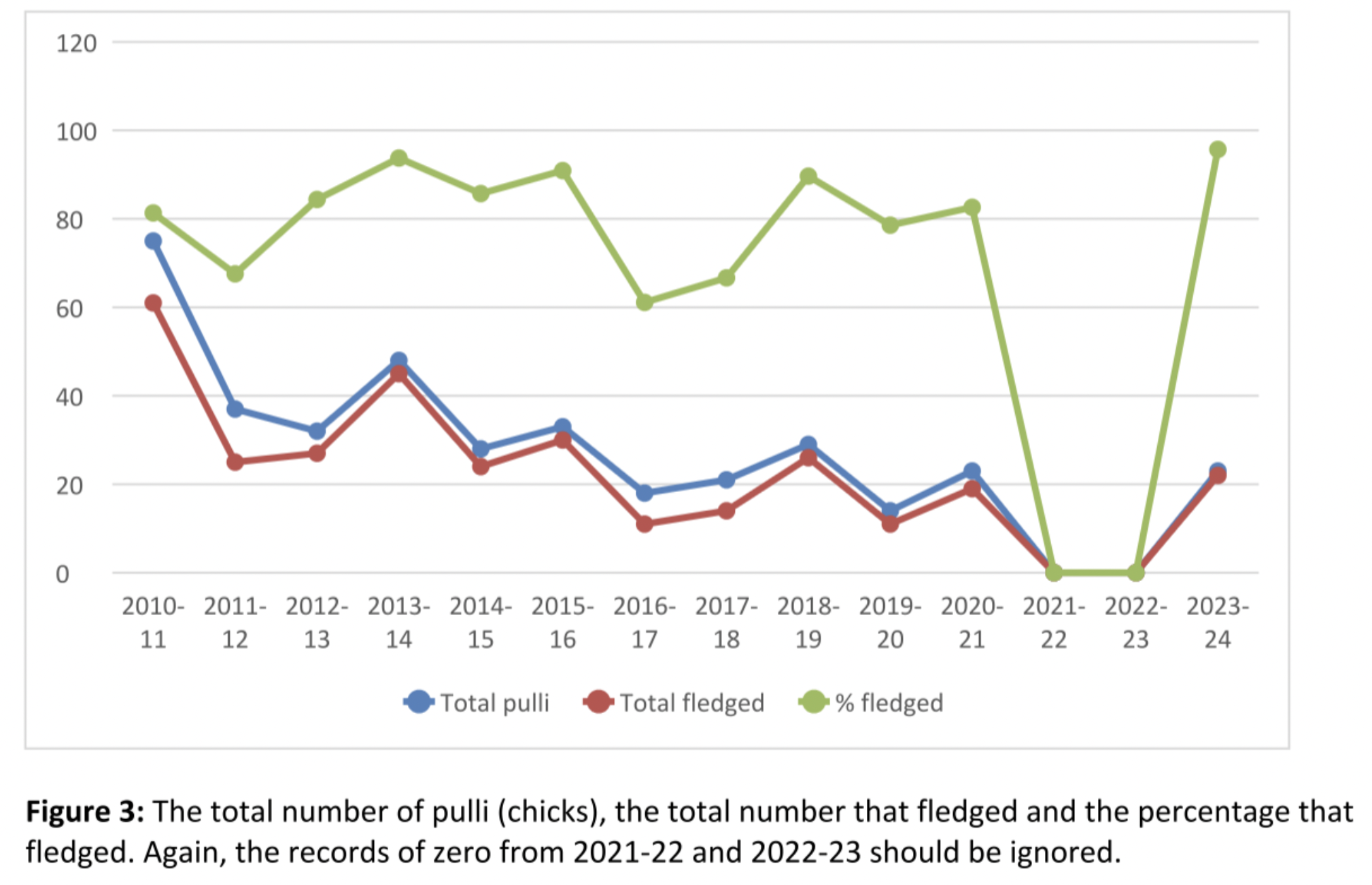

So what can we learn from the years of observation? Figures 2 and 3 are based on data from 2010-11 onwards (excluding the two seasons referred to above). They show that the numbers of eggs and chicks fluctuate from year to year but that there are longer-term trends to observe. Not surprisingly, the number of eggs laid, the number that hatch (Figure 2), and the number of chicks raised to fledging (Figure 3) have declined as the number and percentage of boxes used has declined (Figure 1). But while it is tempting to assume that this is because more natural sites are available, this is probably not the whole story.

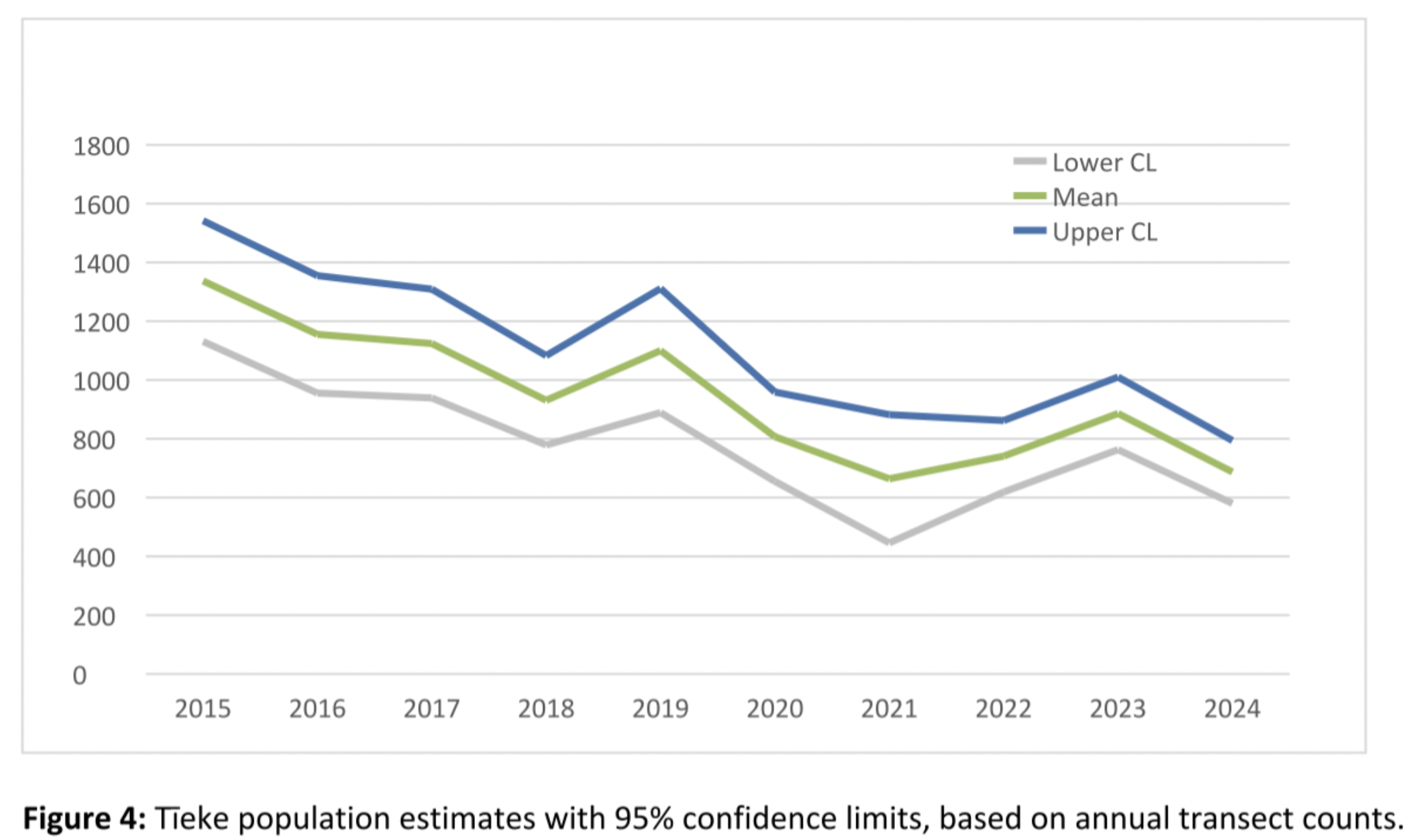

Figure 4 is based on data from the annual bird transect survey, which started in 2015. It shows that, while there have been shorter-term fluctuations, the total population of tīeke on the Island is now slightly more than half what it was in 2015. So the declines observed in nest boxes could simply be a reflection of the decline in population.

Figures 2 and 3 also indicate the percentages of eggs that have hatched and chicks that have fledged. Since 2010, 40-60% of the eggs laid each season have hatched, and a more variable 60-95% of the chicks that hatch each season have been raised to fledging. Last season (2023-24) was the most successful on record, with all but one of the chicks hatched in boxes having fledged.

It is clear from all this that the data from the nest box scheme can inform us about annual and longer-term changes in tīeke breeding behaviour and outcomes, but understanding these changes requires a much broader range of information on other components of the Island’s ecosystem. Some of this is available from Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi projects already underway (such as the transect survey mentioned above), some will come from projects planned for the future, and some is available from other sources (such as local weather records). What is certain is that, to understand what is happening to the tīeke on Tiritiri, we just have to keep checking and counting.

Celebrating 40 years of tīeke/saddleback

Celebrating 40 years of tīeke/saddleback on Tiritiri Matangi

Celebrating 40 years of tīeke/saddleback on Tiritiri Matangi

Author: Stacey Balich, Guide

Date: May 2024, Dawn Chorus 137

Header image credit: John Sibley

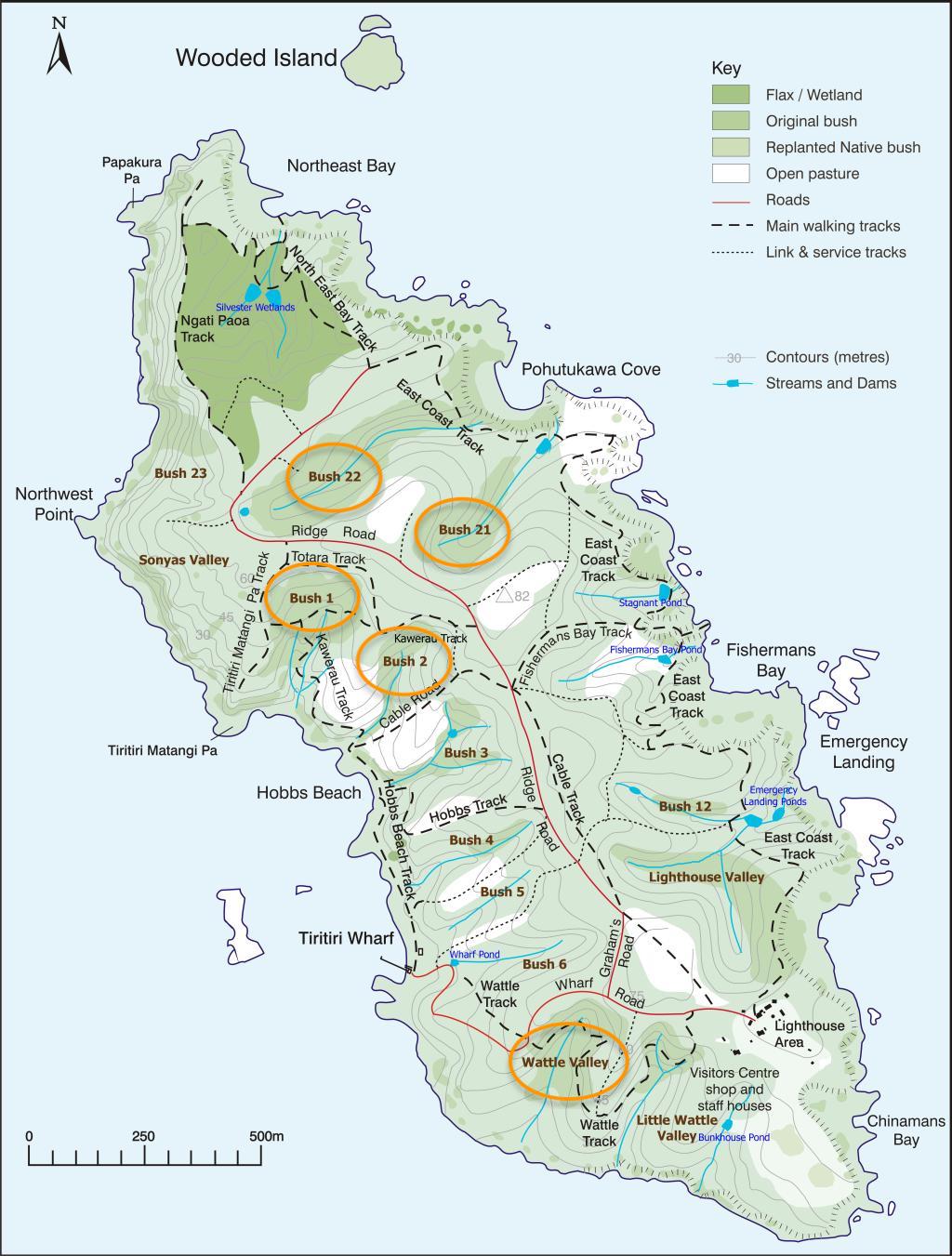

In 1984, 24 tīeke/saddleback from Cuvier Island were released on Tiritiri Matangi. They quickly established themselves with the help of nest boxes, roost boxes and regenerating bush. This year marks the 40th anniversary of their arrival, and, to celebrate this, Barbara Walter shared with me her experiences and stories from the early years. Dr Tim Lovegrove (Auckland Regional Council Heritage Department scientist) coordinated the translocation from Cuvier Island. The 24 tīeke, comprising six breeding pairs and 12 juveniles, came from five different areas of Cuvier Island and had distinct dialects. In order to preserve these distinctions, they were released in five different areas on Tiritiri Matangi: Bush 1, Bush 2, Wattle Valley, Bush 21, and Bush 22 (see Figure 1).

At the start, 360 nest boxes were made by the North Shore Forest and Bird branch, coordinated by Eric Geddes, who used to travel to the Island on a small runabout from Army Bay. There were some differences in how the boxes were made. Some were short and some were long, both types having a V shape for the opening. Later a grill was added to the opening to prevent mynas and ruru from getting in, especially ruru, as they were getting in and stealing the eggs. John Craig and Marijka Falenberg were the first to monitor the tīeke, and when Marijka finished John asked Barbara to continue with the project. She remembers going out at night with John and Marijka to monitor the nests, and she couldn’t keep up with them because they had longer legs than her.

Barbara was tasked with the responsibility of checking the boxes once a week during the season, and twice a week when eggs were hatching. This was quite a laborious task, which required a great deal of dedication, attention to detail, and physical exertion. Ray prepared dinner for them on the days when Barbara was occupied with checking the boxes. Barbara and Ray also used to band the tīeke chicks in the nest boxes.

Left image: Figure 1: Map of Tiritiri Matangi Island showing the bush areas. Bush 1, 2, 21, 22 and Wattle Valley are circled.

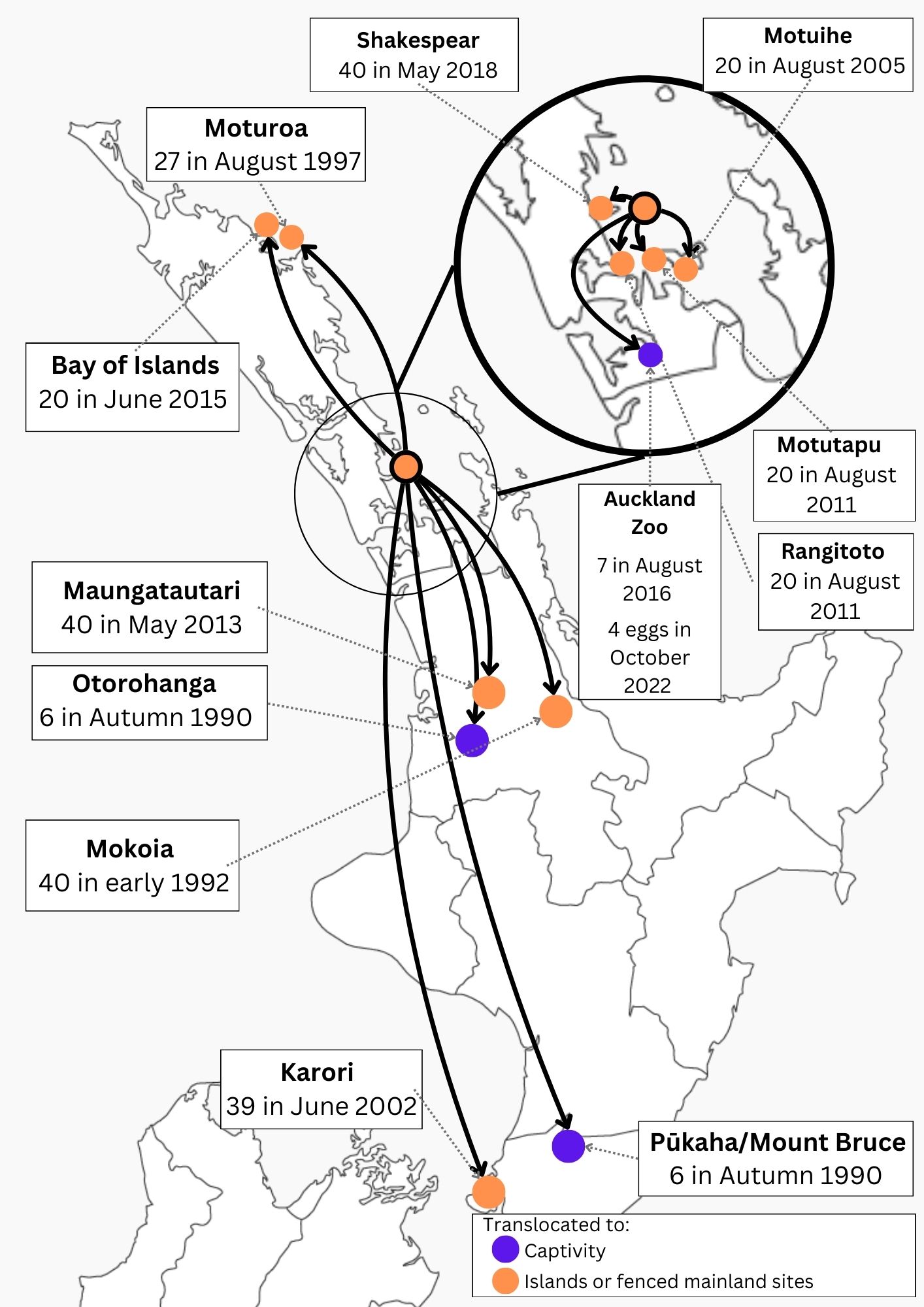

Right image: Figure 2: Map of the North Island showing the tīeke translocations

Left image: Figure 1: Map of Tiritiri Matangi Island showing the bush areas. Bush 1, 2, 21, 22 and Wattle Valley are circled.

Right image: Figure 2: Map of the North Island showing the tīeke translocations

Tīeke are generally long-lived birds. Five or six of the original birds were still being seen in 1994 and two birds seen in 1998 had been banded back in 1978 and 1979. One female in Wattle Valley lived a long and fruitful life, reaching the impressive age of 21. Despite being a loyal and devoted partner, this tīeke had three different mates during her lifetime. Barbara mentioned that during one breeding season, she constructed multiple nests before selecting the perfect one to use.

In 1993, poisoned bait was dropped on the Island to eradicate the kiore (Pacific rat). Prior to this event, it was important to determine whether the tīeke would be likely to be affected by this, so bait was placed in some of the roost boxes. Fortunately, the tīeke showed no interest and the bait drop caused them no harm.

Photo credit: Kathryn Jones

A thriving tīeke population

During the early years, tīeke used to lay three or four eggs per nest. However, over time, Barbara noticed that the number of eggs laid gradually decreased. It is now known that this decrease in egg-laying is a natural mechanism that helps regulate the population of tīeke. By laying fewer eggs, tīeke can ensure that the number of chicks hatching each year is balanced with the available resources in their habitat.

By the 1990s, the tīeke population was thriving. As the trees grew taller they had more natural places to build their nests, such as in the punga and harakeke/ flax bushes. In 1991 there were 60 pairs who produced 117 chicks and during the next season, there were 147 chicks. As a result of this productivity, the Island became a source for translocations to other sites. Barbara described how mist nets were put up and tīeke calls were played to attract the birds to catch them for translocations. The first translocation, to Otorohanga, took place in 1990, and many successful translocations followed (see Figure 2 above). Barbara remembers Ray being asked to go with the tīeke to Moturoa in the role of kaumātua.

Barbara said that she found herself busy with the planting and handed the monitoring over to Morag Fordham, who had been outstanding and, without

her help, the Island’s tīeke programme would not have been the huge success it has turned out to be.