The Sometimes Missing ‘F’ Word: Fauna, Flora, and Funga

Written by Stacey Balich, based on the Tiritiri Talk presented by speaker Peter Buchanan.

We were thrilled to welcome Peter Buchanan from Manaaki Whenua, Landcare Research as the guest speaker for this season’s Tiritiri Matangi Talk. His engaging presentation, “The Sometimes Missing ‘F’ Word: Fauna, Flora, and Funga,” opened our eyes to the often-overlooked world of fungi and its essential role in our ecosystems. Around 80 people gathered to hear Peter’s fascinating insights, making it one of our most well-attended and thought-provoking talks to date.

Peter opened with a surprising revelation: the largest biological kingdom on Earth isn’t flora or fauna—it’s fungi. In biology, a kingdom is one of the highest levels of classification, grouping together all forms of life with shared fundamental traits. Fauna (animals) ranks first, funga (fungi) second, and flora (plants) comes in third, challenging the way many of us think about the natural world and its major players. He explained that fungi are so abundant and ecologically important that, in April 2024, National Geographic officially adopted the term “funga,” giving fungi equal footing with flora and fauna in biodiversity conversations.

He went on to explain the powerful role of symbiotic fungi, particularly in native forests of beech, mānuka, and kānuka. These fungi form mutually beneficial partnerships with plants, helping them absorb water and nutrients through vast underground networks called mycelium. The fungi, in turn, feed on carbohydrates provided by the plants or from decomposing leaves. These thread-like fungal cells, called hyphae, spread out through the soil, massively increasing the area that plant roots can access, making the forest floor a complex web of interdependence and nutrient exchange.

Peter also discussed lichens, which are not a single organism but a partnership between fungi and algae. The fungal structure provides a framework, while the green algae component captures sunlight to create energy. Without the fungi, the lichen wouldn’t exist, it’s this partnership that allows them to thrive in harsh and nutrient-poor environments.

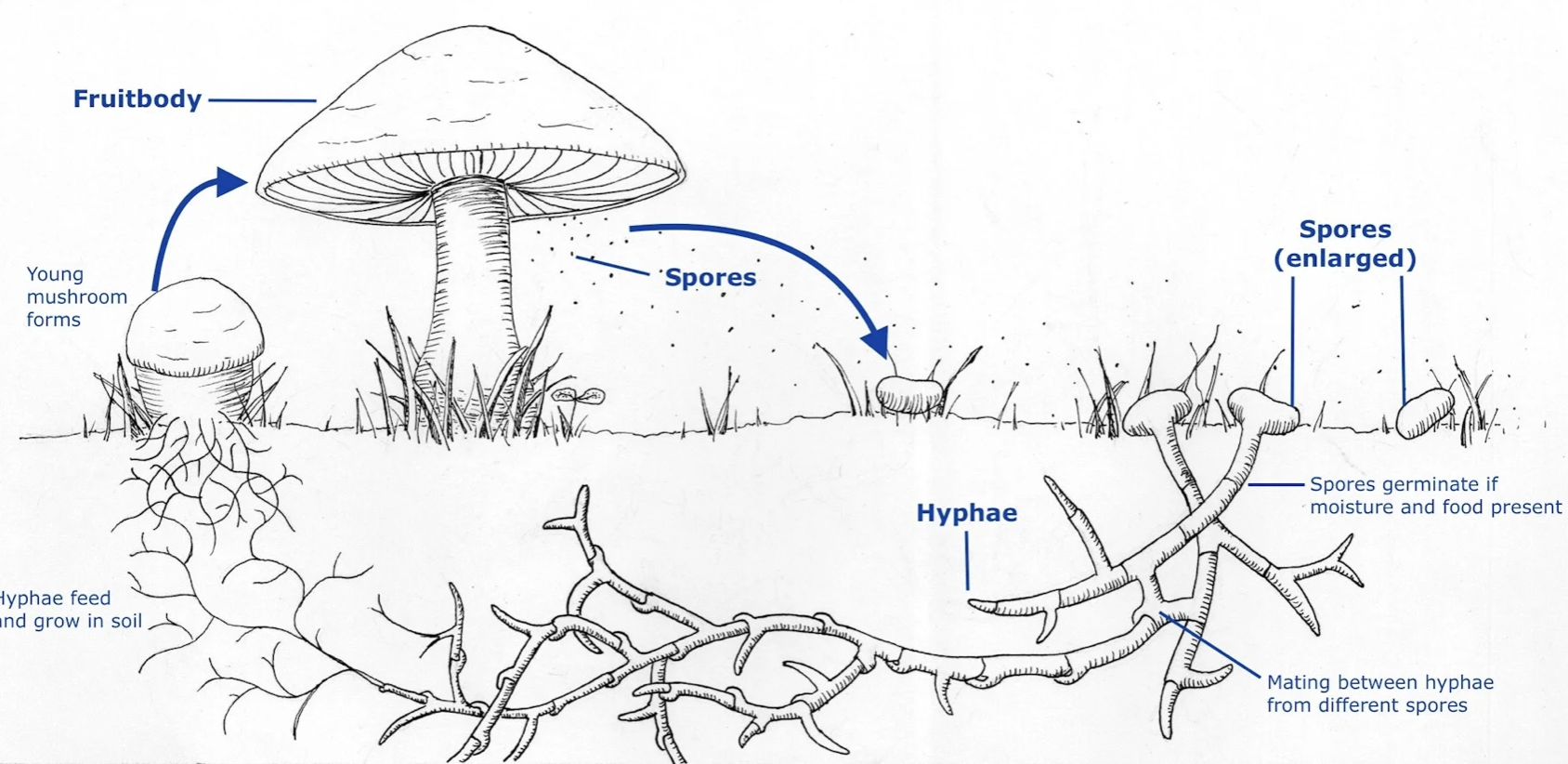

He reminded us that the mushroom we see above ground is just the fruiting body, its purpose is to produce and release spores, much like a tree flowering to make seeds. The majority of fungus lives below the surface as mycelium, working constantly to break down organic material and sustain forest health.

The talk also touched on parasitic fungi, such as myrtle rust, which arrived in New Zealand from Australia in 2017. It has caused widespread damage to native myrtle species like pōhutukawa, ramarama, and mānuka. Peter also noted Armillaria, a native fungus that causes root rot and affects commercial crops like kiwifruit. These are examples of pathogenic fungi, those that cause disease.

In contrast, saprobic fungi play a vital role in decomposing organic material and cycling nutrients back into the forest. However, Peter cautioned that artificially adding mulch to forest environments can disrupt these natural cycles, as mulch may attract non-native fungal species and change the native balance.

A highlight of Peter’s talk was a remarkable photograph he took during the 2025 New Zealand Fungal Foray at Rotokare, near Eltham. It featured a gigantic Ganoderma bracket fungus, 82 cm wide and 45 cm thick, estimated to be around 30 years old. Even after decades of research, Peter admitted he’d never seen one so large. The discovery was a vivid reminder of how quietly and powerfully fungi shape our landscapes over time.

Peter highlighted the astonishing fungal diversity in Aotearoa. For every one species of vascular plant, there may be up to six fungal species, meaning there are likely tens of thousands of fungi in New Zealand, many yet to be formally described.

He also honoured mātauranga Māori, traditional Māori knowledge of fungi. He shared that:

- Te pūtewa, a bracket fungus, was used as tinder and for wound care.

- Te pekepekekiore, ear-like fungi, were used as food.

- Te matakupenga, the net-like basket fungus, could be eaten in its early “egg” form.

- Te Āwheta, a parasitic fungus, was used to create black pigment for tā moko (traditional tattooing), when mixed with charcoal and bird fat.

- Cyttaria, a parasitic fungus on southern beech, is a seasonal food for kererū.

Another significant species is te hakeke, or wood ear fungus (Auricularia), nicknamed “Taranaki wool.” It holds the distinction of being the only native mushroom commercially exported, thanks to Chinese merchant Chew Chong, who collected and exported it between 1875 and 1885. There is a fantastic museum in Taranaki, Tawhiti, that tells this story in more detail.

Peter also broke down the lifecycle of a mushroom:

- Spore dispersal – Mushrooms release spores into the environment.

- Germination – Spores develop into hyphae.

- Mycelium formation – Hyphae fuse and grow into a mycelial network.

- Fruiting – The mycelium produces mushrooms above ground.

- Spore release – The cycle begins again.

He added that fungi reproduce sexually when compatible hyphae (like male and female types) meet and exchange genetic material, further revealing how complex and life-like fungal systems can be.

A particularly heartwarming moment came when Peter shared how he had contributed feedback to the Reserve Bank during the redesign of the $50 note. In the earlier design, te werewere kōkako, a stunning blue fungus, was partially obscured. Thanks to his advocacy, it now features prominently. He also shared the beautiful Māori kōrero that the kōkako bird’s distinctive blue wattles came from brushing against this blue fungus while feeding, tying together the bird and the fungus in name, legend, and colour.

To conclude, Peter highlighted why conserving fungi is essential for ecosystem health. Today, 45 New Zealand fungi are assessed by the IUCN Red List, and nine are listed as endangered. These include:

- Calostoma fuscum (Fischer’s egg),

- Ganoderma, the pukatea bracket fungus, last seen in 1972,

- and Hypocreopsis amplectens—the critically endangered “tea tree fingers.”

Peter closed with a look at New Zealand’s two major fungal collections:

- The New Zealand Fungi Herbarium in St Johns, holds over 110,000 dried specimens, many kept frozen, with data freely accessible to the public.

- The International Collection of Microorganisms from Plants (ICMP), which contains 11,000 living fungal cultures, supports both science and conservation.

Peter’s talk was a powerful reminder that fungi are not just background players in nature, they’re architects of ecosystems, keepers of culture, and unsung heroes of biodiversity.